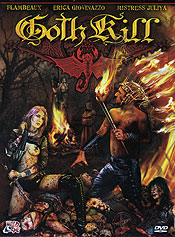

Goth Kill/Goth Kill: The Soul Collector (2009) **

Goth Kill/Goth Kill: The Soul Collector (2009) **

A couple of months ago, I started to write a really scathing review of Goth Kill, a long-in-the-incubator micro-budget feature from New Yorker J. J. Connelly. I got bogged down with another review that I’d specifically meant to include in that update, though, so Goth Kill went back in the pile for reconsideration at a later date. Now that that later date has arrived, I find that I’m somewhat better disposed toward this movie than I was the first time around. It seems a little less structurally awkward, a little less tonally and philosophically incoherent, and the lopsidedness between the overbroad but charismatic performance of the lead actor and the atrocious immobility of everybody else now looks a tad less destructive than I had initially judged it. You still won’t see me giving Goth Kill anything like a recommendation, but neither am I inclined any longer to condemn it as utterly worthless.

That charismatic but overbroad lead is a professional fire-swallower who calls himself Flambeaux!— don’t forget the exclamation point— and his character is just the kind of guy from whom overbroad charisma ought to be expected. Nicholas Dread is the effectively immortal leader of a Satanic cult, but he came to his vocation by a roundabout route. In fact, in his first incarnation, he was a friar in service to the Irish branch of the Papal Inquisition. Brother Nicholas, as he was then known, had as much talent for torturing a bogus confession of witchcraft or heresy out of a nobleman’s daughter as anybody, but he was also a questioning sort— enough so to make his boss, Father Connelly (Final Edition’s Frank Dudley), most uncomfortable. Eventually, that questioning nature made Dread one of the few perceptive blokes to catch on to the scam the Church was running, exploiting the class resentments of the peasantry to line the bishops’ pockets with property confiscated from weak and unpopular landed families. Brother Nicholas even attempted to reform the Inquisition from within, but all that got him was a stake beside that of the last “witch” to be burned on his watch. Thus did Nicholas Dread make the exact opposite of the usual deathbed conversion, renouncing God and all His works, and striking a rather more elaborate bargain with Satan than one might expect the rapidly rising flames to permit. The terms of this deal were as follows: 1. Dread was to rule over a kingdom of 100,000 souls in Hell; 2. Dread must populate that kingdom himself by murdering 100,000 people deserving of damnation; 3. Dread was to be reincarnated continually until he had satisfied condition 2, at which point his next death would become final, and he could enter the Inferno to claim his prize. Since that day, Nicholas has lived many lifetimes, appearing in many guises, diligently harvesting corrupt souls with the occasional aid of a pair of devil girls who might have stepped alive and breathing out of a Chris Cooper pinup.

All of that will be revealed to us piecemeal over the course of the film, usually in great, inelegant lumps. As we join the action, Nicholas is rounding up the last couple dozen of his future subjects, calling an assembly of his coven in what I take to be an out-of-the-way corner of Central Park, and mowing the lot of them down with a repeating shotgun. He’s swiftly apprehended, but that was part of the plan. So too were his conviction on multiple counts of premeditated murder, and his consignment to death row on Riker’s Island. After all, Dread is still a young man in his current incarnation— why wait around on Earth another 50-odd years when his kingdom awaits in the next world? The sole bit of business left to be conducted in this life can be squeezed in at Riker’s under the pretext of last rites. There was one follower whom Dread did not invite to the Central Park massacre— the “witch” who burned along with him all those centuries ago (Julie Saad), who must have done a little Satanic haggling of her own on the way out— and he wants to pass along to her the grimoire that enabled his multitudinous resurrections. I guess it doesn’t hurt, at that, to have a contingency plan when dealing with the Devil. As it happens, a contingency plan for the contingency plan would not have been overdoing it. When Nicholas gets to Hell, he discovers that he’s been swindled but good. Far from a nation of the damned at his beck and call, he is greeted by an infinite expanse of empty limbo. Not only that, but his pet witch gets run over by a passing car on her way home from Riker’s (with blackly apt irony, the driver of said car is a Catholic priest), and the grimoire is stolen by a homeless crackhead.

Meanwhile, eighteen-year-old Annie Caldwell (Erica Giovinazzo) moves to the big city to live with her slightly older and considerably worldlier friend, Kate (Eve Blackwater). Kate has attached herself of late to the New York goth scene, and she is eager to introduce Annie to its morbid and vinyl-enshrouded delights. Of course, Annie is going to need some vinyl-enshrouding of her own first if she’s to avoid making an ass of herself and Kate alike, so the first thing we see the two girls do together is to go out and get Annie some suitably skanky new duds. While they’re shopping, the proprietor of Kate’s favorite boutique hands her a flyer for a party at a nightclub called the Cellar. This isn’t just any party, either— it’s a Scorpion Society party! “Huh?” you say? Well, the Scorpion Society purport to be a vampire clan. They’re such cosmic-scale wankers that even Kate sees through them a little bit, but they think of themselves as the crème de la sang of the goth scene, and their parties are very difficult to get invited to. Being given the flyer is therefore a validation of sorts, and we all know how teenagers crave validation. We also know how Kate and Annie will be spending Friday night.

The party at the Cellar is pretty much what every terrified suburban parent imagines goth gatherings to be. The presence of so many obviously genuine goths among the extras suggests that all concerned are in serious danger of getting their tongue barbells entangled with the posts of their cheek studs. In any case, Kate and Annie both catch the eyes of DJ Demon (Anastacia Andino— also Goth Kill’s casting director) and Bad Bob the bouncer (Tom Velez), and the girls are singled out for the “honor” of an audience with Lord Walechia (Michael Day), the founder of the Scorpion Society. My contemporaries who grew up in the Washington DC television market will know at once what I mean when I say that Lord Walechia is more Count Gore de Vol than Count Dracula; the rest of you are invited to Google it. Acting on orders from DJ Demon, the bartender drugs the newcomers’ wine, nominating them the centerpiece of the bullshit Rohypnol-rape Satan-orgy that is the evening’s true main order of business. Lord Walechia has something extra to spice up tonight’s ceremony, too. He scored big at a pawn shop the other day, picking up an extremely old book full of authentic-looking black arts incantations and formulae. Before commencing the dope-coerced sex, Walechia has his followers join him in reciting an invocation from the book. What Walechia fails to realize is that the antique volume is Nicholas Dread’s stolen grimoire, and that the text he and his minions are chanting— “Og ot yadnus loohcs” (You know how fond Satanists are supposed to be of back-masking? Well, read each word of the incantation backwards, and see what you get.)— is the spell that will free Dread from his confinement in Hell and give him license to possess a new body. Annie’s, for example. And since it just so happens that Lord Walechia used to be one of Dread’s lackeys before breaking with that cult to form the Scorpion Society, Nicholas knows just where to begin his second attempt to establish his own infernal principality.

That last part is where Goth Kill still loses me. It’s a neat idea that evildoers have a legitimate role to play in the moral structure of the cosmos, punishing each other for their misdeeds both in this world and the next. And within that context, I can buy into the notion of someone who thought he was one of the good guys realizing one day that he’s really evil instead, and deciding to roll with it on certain specific terms after his bid for atonement is thwarted by the very people whose villainy he used to abet. But what I can’t force to make sense the way it’s presented here is why Nicholas keeps working to earn his vassal state in Hell even after Satan reneges on his end of the bargain, nor can I see any reason why Ultimate Evil, having already fucked Dread out of the 100,000 souls originally stipulated, should scruple at fucking him out of 20 or 30 more after the throwdown with the Scorpion Society. The only thing I can think of— and let me emphasize that there’s nothing in the film itself to indicate that this was J.J. Connelly’s intention— is that it isn’t Satan who grants Nicholas his greatly attenuated Hell-kingdom in the end, but God, presumably in reward for Dread’s remarkably scrupulous treatment of Kate and Annie once he’s settled his accounts with Lord Walechia. In fact, I really wish that were what Connelly was driving at, because it would make Goth Kill the most theologically interesting horror movie I’ve seen in ages, whereas the way things stand, it can merely be read that way if you squint hard and concentrate. Goth Kill vaguely implies a metaphysical universe based less on duality between Good and Evil than between Law and Chaos, in which a principled evildoer can win divine favor by stubbornly sticking up for the system’s rules, and performing his duties as defined by them even in the face of backstabbing and opposition from his own side. But with a concept as unusual and thought-provoking as that, I’d really prefer something better than vague implications— especially when most of them look to have been almost totally accidental in the first place.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact