Georges Méliès Trick Films, 1896 [unratable]

Georges Méliès Trick Films, 1896 [unratable]

Popular entertainment has an ecology, just like the natural world. Forms and styles, genres and sensibilities arise, burgeon, and decline in response to the pressures of their cultural environment. They spread from one territory to another, adapting to local conditions, and evolve both convergently and divergently over time. Occasionally, they even become commercially extinct. Cinema, being among the youngest of the arts, has not had time to experience too many such extinctions, so it is all the more noteworthy that its dead should include a pair of proto-genres that had accounted between them for the majority of all movies to see release during the days of their greatest popularity. Perhaps more remarkable still is that movies of both types continue to be made in incalculable numbers today, even though few if any are ever shown publicly to a paying audience. I’m talking about actualities and trick films.

The actuality is arguably the most primitive form of cinema, and has its origin in the period when filmmakers, almost by necessity, were more engineers than artists. These were the films in which Auguste and Louis Lumière principally dealt, simple visual recordings of occurrences, whether staged or authentic. Novelty was the key to the actualities’ popularity, both the novelty of the motion picture itself and the novelty of faraway places and unusual events. In an age when most people spent their whole lives within a few dozen miles of their birthplaces, the actualities literally changed the way their viewers saw the world. Suddenly, it was possible for the average person to see things that they could previously only hear or read about, and to have, for the price of a few pennies, vicarious versions of experiences that had once been obtainable only by undertaking expensive, often arduous, and sometimes even dangerous journeys. Of course, the very success of cinema set up the decline of the actuality, for the more accustomed the public became to movies, the less interest the unadorned concept of the motion picture retained. People still wanted to see exotic and exciting things, naturally, but audiences started to expect more sophisticated presentations as the 19th century gave way to the 20th. To continue capturing the pocket change of these increasingly demanding audiences, the “true” actuality had to evolve into the newsreel and the documentary, while its staged counterpart had to begin emulating the real stage, incorporating plot, characters, dialogue, and all the other appurtenances of traditional drama. The actuality never really went away, however— it just ceased to be viable as a commercial enterprise. Anyone who ever filmed his child’s first steps, videotaped her father’s retirement ceremony, or performed any of a thousand other commonplace acts of documenting daily life in moving pictures has made an actuality, whether they thought of it in those terms or not. Also, one might make the case that there are a couple of very narrow fields in which the actuality can still command a few paying customers. Pornography, certainly, has been evolving into an actuality-like form ever since the advent of hardcore at the turn of the 70’s, like a tapeworm abandoning muscles, nerves, and digestive organs, and the likes of Bumfights and Girls Gone Wild could conceivably be spun as a distinctively 21st-century genus of actuality, as well.

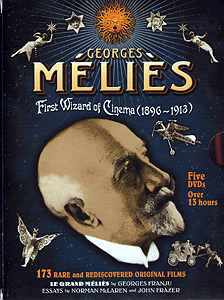

Trick movies, too, persist on an amateur basis, every time a novice filmmaker experiments with stop motion or forced perspective or any of the various compositing techniques. The difference, once again, is that in the 1890’s, such camera trickery was novel enough to attract an audience all by itself, without the aid of any more story than was needed simply to establish context for the illusion, and once again, the gradual habituation of audiences to the basics of moviegoing was enough to push the state of the art onward toward higher levels of complexity as time passed. Trick movies survived longer in the marketplace than actualities, however, not least because they were inherently more flexible. Actualities showed only things that did or could exist, even if they didn’t or couldn’t exist anyplace where their viewers might credibly go. In a trick movie, on the other hand, the only limit was the filmmaker’s ingenuity. No 19th century filmmaker was more ingenious than Georges Méliès, best remembered today for his remarkable Jules Verne and H. G. Wells-inspired fantasy, A Trip to the Moon. Méliès had already been in the movie business for six years when he made that film, however, producing literally hundreds of short subjects, the majority of them broadly suitable for inclusion in the trick film category. Virtually all of the surviving Méliès material is now available on DVD in a superb five-disc box set from Flicker Alley, together with a supplemental disc collecting two dozen or so movies that were not obtainable in time for inclusion in the main set, and I’ll be working my leisurely way through this treasure trove of antiquities in the months to come. The really brief movies I’ll bundle together into year-by-year omnibus reviews like this one; the more substantial pieces will receive correspondingly more substantial treatment.

Only six films from Méliès’s first year seem to have survived, and one of those is probably in somewhat fragmentary form. Felicitously, one of the survivors is the very first movie Méliès offered for commercial exhibition, enabling us to see just how rapidly he grew as a filmmaker. That first film, a minute-long actuality called Playing Cards/The Card Party/Une Partie de Cartes, appears to be a remake of an early Lumière Brothers production (what do I keep saying about everything being older than you think it is?), and is of very little interest today except as a baseline for comparison with future works. A bunch of guys sit around a table in a garden, playing cards for a minute and seven seconds; at one point, a woman comes around to serve them drinks. Modern viewers will care not a bit, except insofar as they’re curious about how little it took to entertain a cinema audience in the early months of 1896. The slightly later Post No Bills/Défense d’Afficher is a bit more edifying, in that it at least revolves around a joke. An ad-man sneaks up to paste a poster onto the wall of a public building— directly over the stern warning to “POST NO BILLS” painted across said wall— when the soldier standing guard over the place moves along to the next stage of his rounds. A second ad-man follows, covering up the first poster with a much bigger one promoting a show at Méliès’s Theatre Robert Houdin, and the two of them get into a tussle, splashing each other with their paste buckets, among other things. The ad-men scurry off as the soldier returns, and then the latter’s commanding officer walks by, sees the poster on the wall, and chews the oblivious guard out for permitting such vandalism on his watch. It’s very much the sort of thing that gave rise to the common misperception that silent movies were invariably corny slapstick comedies built around slight sight gags, and Post No Bills could just as well have been made by any other 1890’s auteur. It’s with the remaining four films that Méliès starts showing his credentials for the title that the Flicker Alley box set bestows upon him— the First Wizard of Cinema.

In A Terrible Night/Une Nuit Terrible, a man played by Méliès himself climbs into bed after what we may presume to be a long and exhausting day, only to discover that he has company in the form of a huge insect that crawls up the sheet, across the horrified man’s body, and eventually up the wall beside his bed. The man smashes the bug with the broom he keeps beside the bedstead, but it falls directly into his lap, still not quite dead. Again and again he smacks the bug, finally disposing of its flattened carcass in the chamber pot under the night stand. Even then the ordeal is not over, though, for now the bedclothes are thoroughly contaminated with bug guts, and the frazzled would-be sleeper has to scrape them all off with the sole of his slipper before he can get any rest. A Terrible Night is a charming combination of broad physical comedy and pure gross-out, and it’s an unexpected pleasure to encounter a big rubber bug so early in the history of special effects. Méliès’s six-legged nemesis rather resembles a king termite expanded to the size of a man’s hand, clumsy and hulking, with a fat, stripey abdomen that looks like it would indeed generate nauseating amounts of sticky glop when squashed. It’s plainly being controlled by the simple expedient of a puppeteer above the frame dragging it along on strings, but the undeniable fact remains that we’ve all seen plenty of rubber bugs much worse than this one in movies made many decades later than A Terrible Night. If nothing else, the bug puppet deserves props for having six independently movable legs! Méliès the actor, meanwhile, displays an unexpected knack for throwing himself about in a humorous yet remarkably athletic manner, although the heavy makeup he wears (including a false nose that looks almost like it was made out of some manner of squash) suggests that he didn’t quite trust his own clowning abilities at this stage of his career.

The Vanishing Lady/Escamotage d’une Dame au Theatre Robert Houdin is, as its French title implies, nothing more than a cinematic take on an illusion that Méliès frequently performed as part of his magic act. It is thus a trick film in the purest possible sense of the word, and is prevented from being also an actuality only because the technique Méliès employs to effect the trick here is one that he did not and could not use onstage. He and his longtime assistant, Jeanne d’Alcy (who would become the second Mrs. Georges Méliès in 1925), step out onto the stage (or rather, they step out in front of a backdrop painted to resemble the stage) at the Theatre Robert Houdin, at which point d’Alcy sits down in a chair at the center of the frame. Méliès drapes a blanket over her, executes some typically “magical” gestures, and yanks away the blanket to reveal the now-empty chair. Next, Méliès conjures a blackened and moldering skeleton into the chair, and repeats the blanket-draping process on the skeleton to bring back d’Alcy. The mechanism behind The Vanishing Lady is perhaps the most basic of all special effects, the stop-substitution, in which the camera is turned off and some actor or prop is added, removed, or replaced before shooting begins anew. The notable imperfection with which it is performed in d’Alcy’s disappearance, meanwhile, shows how easy it is to screw the trick up, even despite its conceptual simplicity. The slightest shift in pose while the camera is turned off to set up the substitution, or the smallest failure of the performers to hit their marks when filming resumes, and the illusion is spoiled. Here, it’s the blanket that causes the problem, for although Méliès manages to hold it stock still for however long it took d’Alcy to get out from under the thing, he fails to cover her completely in the moment before the camera-stop, so that we can see that she’s gone before what was supposed to have been the big reveal. The two subsequent substitutions work better, though, and it is in any case quite possible that an 1896 viewer would not have had the special effects savvy to spot the initial flub to begin with.

For my purposes, the Main Event among the surviving Méliès productions of 1896 is The Devil’s Castle/The Haunted Castle/Le Manoir du Diable. The Devil’s Castle is sometimes put forward as the first horror movie, and at first glance, it does seem a fair contender for the title, what with all the devils, witches, ghosts, and bats-on-strings. I myself take issue with that identification, though. Horror is at least as much a matter of intent as it is one of subject matter, and nothing in The Devil’s Castle particularly suggests that anyone outside the world of the film was supposed to be frightened by any of its diabolical tomfoolery. However one wants to classify it, though, The Devil’s Castle unquestionably represents a major leap forward in Méliès’s ambitions as a filmmaker. Whereas the last two movies we considered used but one trick apiece, The Devil’s Castle combines the techniques of puppetry and stop-substitution to put on a veritable magic show. It begins when a bat-on-a-string (which, again, is no worse than those in, say, The Devil Bat, despite the 44-year technological advantage enjoyed by the latter film) flits into a castle’s courtyard, where it transforms into the Devil. (It is generally supposed that Méliès played the Devil here, as he so often would throughout his career. I don’t believe that’s so, however, for another character whom we’ll be meeting later looks a lot more like Méliès to me.) Satan conjures an enormous cauldron, and then an imp to stoke it for him; when the imp’s job is done, a synthetic woman (Jeanne d’Alcy again) pops out of the pot. The Devil ushers everybody out of sight, though, when he hears the approach of a knight (this is Méliès, unless my eyes deceive me) and his squire. Evidently interested in moving into the castle, the noblemen take a look around, and are beset by various demonic molestations— furniture that won’t stay put, skeletons that appear out of nowhere, that sort of thing. Then Satan makes his presence known, and summons up both his imp and a platoon of ghosts to subject the intruders to further hassle. Next, the synthetic woman returns, and responds to the knight’s attempts at wooing by turning into a hideous witch. More witches soon join her, and the squire decides he’s had enough, fleeing the castle like his ass were on fire. Finally, the knight grabs a cross from one of the walls, and drives the Devil away.

It’s not quite clear to me how much of The Devil’s Castle we have today. The version that appears on the Georges Méliès Encore disc is in obviously terrible condition, and runs only a minute and fourteen seconds. That’s perhaps half of the longest reported running time (for example, Denis Gifford, writing in A Pictorial History of Horror Movies, gives the original length as “less than three minutes”), and although the hand-cranked nature of 1890’s movie projectors would almost inevitably introduce variations in running times from one presentation to the next, it hardly seems as though any two projectionists could be that far out of synch. Furthermore, the ending that has traditionally been described differs significantly from what we see on the Flicker Alley disc— Satan merely backs away from the cross here, rather than vanishing in a puff of smoke. On the other hand, The Devil’s Castle was among the missing when Gifford was writing, and there’s no good reason to assume that 1890’s reviewers were any more immune to getting the details wrong than their modern counterparts. And of course, the lack of any but the sketchiest narrative in The Devil’s Castle makes it difficult to spot places where something might have gone missing. But whatever fraction of the original movie this is, it still acts as a more or less satisfying whole, and shows how much fantasy could be realized by a sufficiently imaginative filmmaker, even with only the most limited repertoire of techniques.

The key point about The Devil’s Castle is that Méliès had not yet built his studio at Montreuil when it was produced. The painted flats representing the castle were simply rigged up inside a canvas-screened enclosure in Méliès’s garden, leaving the whole production completely at the mercy of the weather, and precluding anything like the complex mechanical manipulation of the shooting environment that Méliès would perfect later on. The only entries in his cinematic spell-book at this stage of his career were the stop-substitutions and puppetry that had driven The Vanishing Lady and A Terrible Night respectively. The Devil’s Castle is nevertheless an impressive piece of work for all its primitiveness, and it’s easy to forget that you’re really just watching the same trick being played over and over again on different objects and characters. There’s also a whisper of storytelling in the film, however faint and infrequently uttered, which will probably make it automatically more interesting to modern audiences than its predecessors.

Coming after The Devil’s Castle, A Nightmare/Le Cauchemar is a bit of a letdown. As in A Terrible Night, we begin with a comically made-up Méliès lying in bed, but this time his troubles begin only after he enters REM sleep. He dreams that he has been transported to some manner of medieval dungeon, and that there is a pretty girl sitting at the foot of his bed. Méliès immediately begins flirting with the girl, but no sooner does he get close enough to put his arm around her than she transforms into a banjo-playing blackface minstrel! The minstrel begins jumping up and down on the bed, singing and strumming his banjo, then turns into a menacing clown when Méliès grabs hold of him to settle him down and shut him up; the dungeon transforms at the same time into a penthouse with huge picture window leading out onto a gargoyle-studded balcony. The clown runs off through the window, and the full moon pops in to bite Méliès on the hand. Then the clown, the girl, and the minstrel all return, and attack Méliès en masse, triggering his awakening in a bed that really has been smashed to flinders. Once more, it’s just puppetry and stop-substitution, and there’s no more narrative than there had been in A Terrible Night, but a close examination reveals some important advances even so. The stop-substitutions are getting not merely better, but literally bigger as well— the entire set gets switched out three times. And although the huge puppet representing the aggressive Man in the Moon is really pretty terrible, what Méliès has it doing is so jarring and strange that the crudity of the effect can be forgiven. (One suspects that Méliès himself was dissatisfied with the moon puppet, as he would use similar Man in the Moon imagery at least twice more later in his career, doing rather better with each successive iteration.) A Nightmare also presents the first surviving manifestation of the anarchic quality that would increasingly characterize his work in subsequent years. I’m not generally given to stunned guffaws, but A Nightmare won one from me with the mad illogic of replacing Méliès’s dream girl with a blackface minstrel. Besides, whatever its faults, A Nightmare looks pretty dazzling when you compare it to Playing Cards, and consider how little time separates the two films.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact