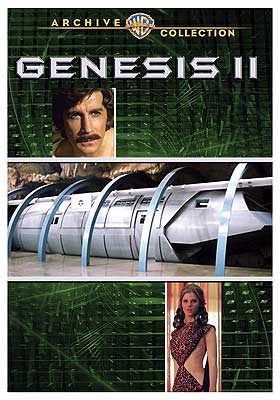

Genesis II (1973) **½

Genesis II (1973) **½

By 1973, “Star Trek” had firmly established itself as a cult hit. It wasn’t yet the big deal that it would become in the 80’s, but it had demonstrated nigh-unprecedented staying power for a show with mediocre first-run ratings that got shitcanned before the end of its third season. Paramount would spend the rest of the decade fumbling toward a way to capitalize on that, and they weren’t the only ones. Gene Roddenberry also decided right around then to try his hand at sci-fi a second time, seeking to parley whatever standing he had as the “Star Trek” guy into a new gig spinning weekly tales of the far-flung future. The genre had changed a lot, though, since the USS Enterprise cruised off into the distance for the last time in 1969. The future had become an anxious place, haunted by the twin specters of ecological collapse and nuclear annihilation, and with very little room for boundless faith in the inevitability of progress. Roddenberry just didn’t have it in him to go full dystopia, though, so the premise for his new series emerged as a strange compromise in which the protagonists would strive to extend the influence of their enlightened society across a world slowly recovering from atomic holocaust. The audience identification figure would be a scientist from just a few years beyond what was then the present day, who Rip Van Winkles his way into the post-apocalyptic 22nd century via a suspended animation experiment gone awry. Fans of old-timey genre television will notice that that sounds an awful lot like Glen A. Larson’s “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century,” which debuted six years later, at the end of the decade. Larson was more in tune with the times than Roddenberry, however, and unlike “Buck Rogers,” “Genesis II” was not picked up for series production. (I’m sure the bosses at CBS thought they were being clever by green-lighting a “Planet of the Apes” TV series instead, but that didn’t work out so well for them, either.) The 70’s were the heyday of the made-for-TV movie, though, so “Genesis II” didn’t vanish completely without a trace. The pilot episode was repurposed as a Movie of the Week, airing for the first time on Friday, March 23rd, 1973.

As James T. Kirk and his crew knew well, the trouble with outer space is that it’s really, really big, and that there isn’t a damn thing in most of it. Absent some way of cheating the speed of light, humans undertaking interstellar travel are apt to go fucking crazy from boredom before they get anywhere, even leaving aside the mismatch between our lifespans and the likely commuting time between any given star and another. The solution, however, is as obvious as the problem— or at least it should be to anyone who ever nodded off during a dull and interminable bus ride: put the astronauts to sleep (or more to the point, into hibernation) for the duration of the trip, and trust the onboard computers to handle routine navigation and maintenance. Of course, humans aren’t bats; you can’t just pop one of us into a refrigerator and take them out good as new three months later. Artificially inducing a harmless, reversible state of suspended animation is a scientific and engineering challenge on par with interstellar space flight itself! But at least one lab has risen to that challenge, under the leadership of Dr. Dylan Hunt (Alex Cord, from The Dead Are Alive and Goliath Awaits). As of August 1979, Hunt and his colleagues have reached the point of readiness for their first trial with a human subject, with the boss himself volunteering to be the guinea pig. In a climate-stable military bunker deep inside Carlsbad Caverns (the better to simulate conditions aboard an actual spacecraft), Hunt will be put into stasis and held there for several days by machines running off a virtually inexhaustible atomic battery. What nobody realizes, however, is that the laboratory lies in close proximity to a long-dormant seismic fault. That fault shifts just minutes after Hunt achieves full hibernation, wrecking the whole facility, killing everyone in it, and burying the suspended animation chamber so deeply that no one even bothers to go looking for it during whatever rescue operations are undertaken afterward.

Dylan survives the tremor, though, and so, impressively enough, do all the machines keeping him alive. He and they also survive the worldwide nuclear war that destroys human civilization a few years later. Indeed, Hunt’s sleep goes undisturbed for 154 years, until the day in 2133 when the underground ruins are discovered and penetrated by a team of explorers led by Primus Isaac Kimbridge (Percy Rodrigues, of Galaxina and Brainwaves). Kimbridge and his colleagues belong to a subterranean society called Pax, which has dedicated itself to recovering as much as possible of the lost knowledge and technology of the 20th century. So naturally a scientist who’s been in cold storage since those days is a hugely exciting find for them, and they do everything in their power to wake Hunt up and get him healthy again.

Kimbridge and the other Primi of Pax entrust the management of Hunt’s recovery to a woman named Lyra-A (Mariette Hartley, from Marooned and Earth II), who like Dylan is an outsider to the underground utopia. On the face of it, that seems like an excellent idea, but it happens that Lyra-A has a rather different perspective on Pax from her hosts. As she wastes no time explaining to Hunt once he’s regained his full strength and faculties, his rescuers are not half as benign as they wish to seem. Using the worldwide supersonic subway system that was the last great triumph of pre-apocalyptic engineering, Pax plunders the globe of its remaining cultural treasures, leaving the struggling societies of the surface world intellectually impoverished and permanently incapable of catching up. And Dylan, in case he hasn’t noticed, is the ultimate cultural treasure. Lyra-A predicts that he’ll find himself a virtual prisoner once the Council of Primi have reached a decision on how best to exploit him. There’s one way out of that predicament, though. The answer to that question on the tip of your tongue about what Lyra-A is doing in Pax if that’s how she regards its inhabitants is that she’s there as a spy for her home country, a city-state of surface-dwellers called Tyrannia. According to her, Tyrannia is the freest, most beautiful place on Earth. If Dylan wants, she’ll help him escape from Pax on its own super-subway, and make the necessary introductions for him to join her people instead.

One quick question, though: why would the freest people on Earth name their country Tyrannia? That’s right, Lyra-A is giving Dylan the bait-and-switch something fierce. Tyrannia is indeed a pretty swell place to live if you belong, as she does, to its ruling caste of mutants. (The Tyrannians’ mutations are mostly internal. They possess dual, independent circulatory systems, giving them superhuman strength and stamina, along with at least highly optimized intelligence.) But the masses still stuck with the original Homo sapiens genome are condemned to squalor and slavery, conditioned to absolute obedience by portable nerve actuators called “stims.” Every Tyrannian citizen carries a stim, enabling them to induce any of eight levels of full-body pain or pleasure at the slightest touch. As that ought to imply, the Tyrannians are no slouches when it comes to technology, but Hunt’s 20th-century technical knowledge is valuable to them just the same. You see, they’ve found something under the mountains, something that keeps Pax Security Primus Yuloff (Titos Vandis, from Satan’s Triangle and Black Samson) up at night worrying whenever he thinks about it. It’s a nuclear missile base that never got off a shot during the Final War, so that its weapons are still sitting there in the silos, just waiting for someone with the know-how to get them working again. None of the Tyrannians possess that know-how, but what about Hunt? Surely he had to have picked up some rudimentary rocketry and computer science during his years working for NASA, and the Tyrannians are very good at making people do things for them. Refusing to help refurbish his captors’ antique nukes quickly gets Dylan remanded to the custody of Slan-N (The Wizard of Baghdad’s Harry Raybould, whom we’ve also seen almost subliminally in The Amazing Colossal Man), a veritable artist of coercion.

All is not lost, though. The reason Yuloff knows about the missile base is because he has spies of his own working undercover in Tyrannia. Two of them— Dr. Kellum (Bill Striglos, of Cutting Class and Tarantulas: The Deadly Cargo) and an albino Comanche giant by the name of Isiah (Ted Cassidy, from Thunder County and The Limit)— have been there for quite some time, attempting to foment a slave revolt. The other, attractive young anti-sex fanatic Harper-Smythe (Lynne Marta of Help Me… I’m Possessed and Blood Beach), was dispatched just recently on a mission to bring Dylan back. Hunt’s experiences in Tyrannia have been such that he refuses to cooperate with Harper-Smythe— not because he has any objection to returning to Pax, but because he’d much rather stick around and help Kellum and Isiah bring Lyra-A’s “freest and most beautiful place on Earth” down around her lying head. He’s got some ideas of his own in that direction, too. The ubiquity of stims among the Tyrannian citizenry suggests to Hunt that there must somewhere be a stockpile of the things. If they could find and raid that stockpile, he and the Pax Underground would have the means to arm who knows how many slaves, and to give their captors a taste of their own medicine.

I thought I detected a few loaded sighs out there when I said that the Tyrannians’ mutations were mostly internal, and normally I couldn’t agree more. What’s the fucking point of having atomic mutants in your movie if they all just look like the regular cast? But let me draw your attention now to the implications of that “mostly.” The Tyrannians do have one external abnormality, which like their enhanced strength and mental alacrity derives from their having two complete, mutually independent circulatory systems. Remember that in most mammals, a developing fetus is indirectly connected to its mother’s bloodstream via the intermediation of the placenta. Since the Tyrannians have two bloodstreams, they also need two placentas, each with its own point of connection, and that, in turn, means that Tyrannians once born have two navels. That might seem like the ultimate weak-ass deformity at first glance, but it’s also a super-bitchy inside joke. You see, Roddenberry’s tenure as the showrunner of “Star Trek” was a constant struggle against NBC’s Broadcast Standards department, which was forever sending down new censorship notes— especially censorship notes related to how head costumer William Ware Theiss planned to dress the Babe of the Week. One recurring point of contention was the visibility of women’s belly buttons, which strange as it may seem was a big fucking deal in the 1960’s. Things were different in the 70’s, though, and Roddenberry decided to celebrate his newfound freedom by having twice as many exposed navels as nature would have permitted. I’m pretty sure this is the only time I’ve ever seen special effects makeup used as an instrument of petty, behind-the-scenes vengeance, and I kind of love it.

Otherwise, love isn’t a reaction that Genesis II is likely to provoke. Don’t get me wrong— it’s mostly adequate as a safe-for-TV interpretation of post-apocalyptic sci-fi, and in a few respects it’s even a little better than that. It’s just that Genesis II doesn’t offer much to get excited about, especially coming on the heels of “Star Trek.” On the upside, it was a smart move to pit utopian and dystopian societies against each other, rather than just picking one unified vision of the future After the End. Furthermore, synopses of the unused “Genesis II” scripts suggest that that would have become a running theme of the series had it been put into full production. Equally smart was giving Lyra-A a chance to present a contrary perspective on Pax. Her description of the good guys’ dark side largely rings true, even if she’s totally full of shit about the character of her own society. That’s a higher level of critical scrutiny than the United Federation of Planets would ever receive under Roddenberry’s management. Most of all, I like the complex interplay of the downer 70’s zeitgeist and Roddenberry’s indefatigable optimism. Most stories in this subgenre depict the post-apocalyptic Earth as a toxic hellhole, but in Genesis II, our planet is a paradoxically edenic place now that humans aren’t running over it by the billion and leaving their shit and garbage everywhere. (Incidentally, the condition of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone these days suggests that Genesis II has closer to the right of it than, say, Damnation Alley.) That could have come across as dark in the extreme, matching in its way anything in The Road, but then against that backdrop stand the people of Pax, who understand the value of the second chance humanity has been given, and who have devoted themselves to rebuilding the world not as it was, but as it might have been. This is the only film of its kind that I’ve seen premised explicitly on the maxim that every crisis is an opportunity in disguise.

It’s a pity, then, that Genesis II apparently didn’t ship with all the hardware needed to hold its pieces together, but did come with a few extra parts that no one knew what to do with. We basically have to take Lyra-A’s word for it when she gives her ominous assessment of Pax, because we don’t really spend enough time there before the “escape” to do otherwise. That has an unfortunate side effect later, when Primus Yuloff gives Hunt a more positive version of the grand tour. We’re stuck taking his word, too, but by that point we’ve been primed to have our guard up, and I for one was not in a “benefit of the doubt” kind of mood. We also don’t spend enough time with Kellum or Isiah, which especially bugged me in the latter case, because I was really looking forward to seeing Ted Cassidy (one of my favorite cartoon voice actors of the 70’s) get a proper live-action speaking part. On the other hand, “albino Indian mystic warrior” is a characterization that could easily go horribly wrong, so maybe the short shrift given to Isiah is actually a good thing. Heaven knows Harper-Smythe’s sex-and-gender-denial shtick wears thin very fast. None of that stuff would matter so much, though, if Genesis II had a stronger lead than Alex Cord’s Dylan Hunt. Hunt’s status as both audience-surrogate outsider and emergent hero puts a tremendous burden on Cord, one which he is simply not up to bearing. Indeed, Cord makes so little impression that he seems less an actor than a life-support system for a moustache. Percy Rodrigues, Ted Cassidy, Lynne Marta, Bill Striglos, and Titos Vandis would have had to grow into one hell of an ensemble to pick up the slack, so I can’t say I’m surprised that CBS weren’t interested in doing this again and again for 20-odd weeks.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact