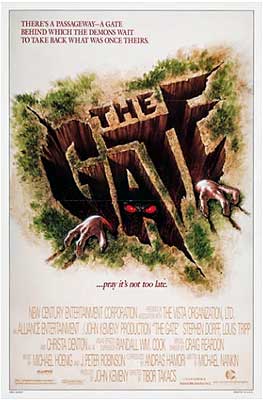

The Gate (1986/1987) **½

The Gate (1986/1987) **½

Most of the movies we’re looking at for this Satanic Panic update accept the panic’s premises, if only tacitly and for the sake of their own. Seriously or not, they assume that heavy metal really is the music of the Devil and his worshippers, that playing Dungeons & Dragons really does lead to madness and tragedy, and that kids celebrating Halloween really do face a night of depredation from demonic forces loose on Earth and maniacs distributing sabotaged treats. The Gate, however, flips the script. The occult metal record that figures in this movie doesn’t call forth the legions of Hell, but rather furnishes the protagonists with both the means to recognize the true nature of their peril and the clues they need to figure out how to send that peril packing. What’s really interesting, though, is that there’s little sign that the inversion represents any conscious intention on the filmmakers’ part to stick up for a maligned art form or subculture. Rather, they seem to have been driven to it unwittingly by plotting necessity. The heroes of The Gate are just an ordinary bunch of suburban teens and pre-teens; in a story without a Van Helsing figure, where the hell else could they come by a working knowledge of demonology except from the liner notes of a Satanic metal album?

One of the kids in question is Glen (a barely pubescent Stephen Dorff, who would appear in Space Truckers and Alone in the Dark as an adult); the other is his best friend, Terry Chandler (Louis Tripp). Each in his way is troubled by things going on at home, but Terry is dealing much less successfully with significantly greater upheavals. His mother died a few years ago, and his globe-trotting father, spatially distant and emotionally inexpressive at even the best of times, has withdrawn deeper still into his work as a coping mechanism. That leaves Terry to fend for himself, which he’s doing by getting a precocious start on adolescent rebellion. Glen’s problem is more commonplace— indeed, it’s practically the universal lot of younger siblings like him. He and his sister, Alexandra (Christa Denton, from a mid-80’s TV version of The Bad Seed), have always been close, but now that she’s in high school, there’s a lot less room in her life for building model rockets with her kid brother and suchlike. And if it doesn’t go without saying that her new best friends, the Lee sisters (Jennifer Irwin and Kelly Rowan, the latter of Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh), don’t get along with Glen and Terry at all, then you must have been an only child.

Glen and Al (Alexandra wishes he wouldn’t call her that anymore…) are coming up on a minor developmental milestone, in that their parents (Deborah Grover, from Mania and Mark of Cain, and Murder in Space’s Scott Denton) are going on a weekend getaway, leaving the kids unsupervised for the first time. Naturally, the siblings have rather divergent expectations of what that means. Glen envisions reconnecting with his sister over the Thunderbolt, the biggest, most powerful rocket they ever began together, which has been sitting unfinished in Al’s closet ever since she discovered shopping malls and boys. Alexandra, meanwhile, is being pushed by her friends into throwing an unchaperoned party, in defiance of her folks’ explicit orders. You will not be surprised to see which vision comes closer to reality.

A weird thing happens a day or two before Mom and Dad hit the road. Just before dawn, Glen dreams that a violent storm catches him up in his treehouse, so that he is crushed beneath the massive old trunk as it falls. When he awakens, he finds that there really was a tempest overnight, and that the wind really did uproot the big tree in the backyard. The really strange part, though, is the hole in the ground left by the root ball. There must be a big void space under the ground there, because the hole won’t stay filled in. Mom and Dad assume that Glen and Terry keep digging it out, but the truth is, any dirt poured into the hole apparently subsides into whatever is down below it. The hole also seems to begin radiating its strangeness out into the world at large. Glen continues having nightmares, and when Terry comes to spend Friday night at his friend’s house, he has them too. Glen and Al’s elderly sheepdog dies under circumstances that probably count as natural causes, but have a distinct whiff of the uncanny about them just the same. And a party trick (Alexandra having fully succumbed to peer pressure as soon as her parents’ car was out of sight down the road) involving “levitating” Glen outperforms the expectations of Al’s friends to a frightening degree.

This is where Satanic heavy metal enters the picture. One of Terry’s most prized possessions is a record his dad bought for him in Europe, the only album by British devil-rockers Sacrifyx. The band all died as eerily as Glen’s dog soon after the record was released, and Terry believes he sees other parallels with the odd goings-on around his friend’s house, too, in the lyrics and liner notes. The latter describe a Lovecraftian regime of ancient monster-gods seeking to reinstate themselves in our reality by means of hidden dimensional gateways linking it to their netherworldly prison. Sacrifyx presumably took a more or less positive attitude toward the prospect of the Old Ones’ return, but they considerately back-masked an incantation meant to forestall it in one of their songs just the same. Terry thinks the hole in the yard leads to one of those gateways Sacrifyx sang about, and that it has somehow come slightly ajar. Obviously it would be incumbent upon the boys to shut it all the way before anything worse than emanations of vague evil have a chance to come through. The ritual of gate-closing doesn’t go according to plan, however. The things on the other side don’t want the dimensional rift sealed, and their interference in the kids’ conjuring opens the portal all the way. At first, only a gang of ugly little imps pour forth from the hole, but surely it’s only a matter of time before something really powerful notices the unobstructed door between the worlds. Meanwhile, even an imp can smash a record or burn its packaging, depriving Glen and Terry of their most effective weapon against the invasion from beyond. And to think that Mom and Dad were worried about Al throwing a party in their absence…

The Gate is an odd one, even disregarding the unorthodox use to which it puts Terry’s Sacrifyx record. It almost feels as if director Tibor Takacs and screenwriter Michael Nankin set out to make a conventional coming-of-age drama, but hastily reworked the project into a horror movie for profitability’s sake. The horror and drama aspects are by no means unconnected (in fact, the bond between Glen and Al ends up being crucial to defeating the Old Ones, via the weirdest literalization of the Power of Love since Krull posited that finding your soulmate confers pyrokinesis), but the scenes serving either purpose don’t really line up tonally with their counterparts.

Surprisingly, the “growing up and growing apart” stuff works significantly better than the “sending the Devil back to Hell” stuff. The siblings’ relationship is very well observed, with acres of emotional territory sketched out in just the lightest strokes. For instance, when Alexandra orders Glen not to call her “Al” anymore, you can sense the entire history of tomboyhood that she wants to put behind her now that she’s in high school, together with all the achingly self-conscious fragility of adolescent identity. It similarly becomes possible to see at once the reasons behind Glen’s pushy neediness. After all, he’s being told in essence that the big sister he’s known and loved all his life no longer exists, and that her place is to be taken by a persona built to the specifications of the hated Lee sisters. Adding Terry to the mix makes for a believably triangular dynamic, as the latter boy— desperate for some closeness and stability in his life to compensate for his dead and distant parents— seeks to exploit the widening gulf between Glen and Alexandra to bind his friend to him that much more tightly. And perhaps most impressive of all coming from a late-80’s horror film, even Alexandra’s new social circle is portrayed with nuance and understanding. They may be just as shitty a pack of losers as any other 80’s B-movie teenagers, but even their worst behavior comes across quite clearly as the forgivable product of much the same insecurity and underconfidence that bedevil Glen, Al, and Terry. The casting of actual teenagers helps a lot in that regard. The high-schoolers’ immature behavior seems more acceptable coming from people who so visibly have a lot of growing to do yet. Meanwhile, the three main characters benefit even more from the age-appropriate casting, especially since the filmmakers managed to find some kids with a fair bit of native acting ability. Truth be told, Stephen Dorff, Christa Denton, and Louis Tripp are probably just playing minor variations on themselves here, but that’s more than adequate under the circumstances. I mean, what better training could there be for portraying the turmoil of adolescence than actually living through it every day?

Mind you, when I say that The Gate is more successful as a coming-of-age story than it is as a horror flick, I don’t mean to imply that it is without value in the latter capacity. Most conspicuously, the Old Ones are quite well realized. The Gremlins-inspired imps are an ingenious reversal of the traditional man-in-a-suit technique for rendering giant monsters, with the costumed stunt performers filmed at an artificially low frame rate to make them appear lighter and nimbler than normal. The giant, multi-appendaged, serpentine arch-demon, meanwhile, is an impressive stop-motion creation harkening back to the most fantastical of Ray Harryhausen’s myth-monsters. It’s an instructive reminder of the old ways’ persistence to see such things in a movie made this late in the 80’s. I also have to give props to the cinematography in the creature scenes, which is much more artful than you’d expect. The trouble is, The Gate’s technical triumphs are let down by an overall lack of suspense. It never feels like the kids are in any real danger, even when some of them have been zombified by the Old Ones’ influence. Meanwhile, the specific manifestations of the beings’ power are oddly small-time considering what they’re supposed to represent. Even the big one with all the arms and tentacles is ultimately just a brute-force threat, and scarcely an apocalyptic one at that. It’s Lovecraftian in the bad sense: just as far too many of Lovecraft’s tales deflate if you don’t share the author’s morbid dread of apes, fish, and black people, The Gate is hobbled by a world-ending menace that barely seems equal to the task of ending a suburban McMansion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact