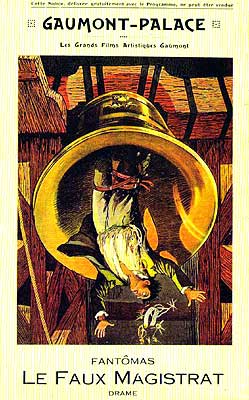

The False Magistrate / Fantomas V: The False Magistrate / Fantomas: Le Faux Magistrat / Le Faux Magistrat (1914) **½

The False Magistrate / Fantomas V: The False Magistrate / Fantomas: Le Faux Magistrat / Le Faux Magistrat (1914) **½

Before Fantomas was a series of films, it was a series of novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre. Unusually, each of Louis Feuillade’s five movies about the character adapts a single, specific book, rather than sampling from all the source material to create an original narrative suited to the demands of the new medium, the way one expects such things to be done today. Considering how early 1913 was in the history of motion pictures, it’s possible that it simply didn’t occur to Feuillade that a composite adaptation was allowed, so to speak. That raises the question of how and why he picked the particular novels he did for the fourth and fifth entries in the series, which adapt books six and twelve respectively. It also raises the question of why he stopped with The False Magistrate, although surely there was no realistic prospect of Feuillade ever getting around to all 32 (!) of Allain and Souvestre’s books. (To say nothing of the eight more that Allain wrote on his own in the 20’s and 30’s, after Souvestre died…) I have no real answer to either query, but after watching The False Magistrate, I tend to suspect that Feuillade and/or his bosses at Gaumont were simply sharp enough to recognize that the franchise was running out of gas on film, regardless of its tireless persistence in print. Although The False Magistrate still has its fantastical notes, this fifth and ultimately final entry in the original cycle of Fantomas movies drifts noticeably in the direction of conventional crime melodrama, with Fantomas pursuing a fairly straightforward blackmail-and-backstabbing scheme. Only the particularly audacious false identity that the villain adopts this time around elevates the crime above something you might have seen covered on the police blotter page of your local newspaper (back when you still had one of those). Instead, Inspector Juve is the one with a plan that only a mad genius could pull off— which is a problem, because the mantle of falsity and puppeteering from the shadows sits uncomfortably on the good guy. It also doesn’t help that Juve’s Fantomas-like anti-Fantomas plot makes absolutely no fucking sense.

We begin, as usual, with a dastardly crime. The Marquis and Marquise of Tergall (some guy called just “Mesnery,” and Germaine Pelisse) have fallen on hard times, as so often happens to those whose wealth is mostly tied up in land and other inherited property. The couple have reluctantly decided to sell the marquise’s extravagant jewelry, for which a dealer in Le Mans has agreed to pay them 250,000 francs. That deal never comes to fruition, because while the marquis is out cashing the jeweler’s check, somebody steals the merchandise right under the latter man’s nose. Incredibly, the thieves perform their heist without ever entering the hotel room where the transaction took place, or apparently opening the bureau into which the buyer had put the jewels for safe keeping until the seller’s return. Fortunately, Morel, the examining magistrate for Saint-Calais who takes over the crime scene and hears witness depositions after the cops have been called, is an old hand at criminal investigation. He quickly discovers a hole in the back of the bureau, which lines up with a hole in the wall separating room 30 (the jeweler’s room) from room 29. 29, incongruously enough, is currently occupied by a priest, and although he claims to have been out ministering to a parishioner when the theft must have taken place, Morel nevertheless considers him the obvious prime suspect. But before the priest can be taken fully into custody, two ladies hurry in from a walk down by the train tracks, bearing vestments stolen from his suitcase, which they saw someone throw from the window of a passing train. The priest is thus cleared, but the jewels are still gone— no doubt speeding their way to someplace along the railway line. Nor is the caper over yet, for the marquis is waylaid on his way home, and relieved of the 250,000 francs.

Framing a priest for a jewel heist and making off with both the jewels and the cash that was supposed to pay for them? If you’re thinking that sounds like Fantomas (Rene Navarre, for the fifth and final time), then Jerome Fandor (Georges Melchior, likewise) agrees with you. And indeed we soon see that the men who jumped the marquis were Paulet (Laurent Morleas) and Ribonard (Jean François Martial), two of the arch-criminal’s known accomplices. But as Inspector Juve (Edmond Breon) surprisingly responds when the reporter goes to him with his suspicions, Fantomas is currently serving a life sentence in Belgium’s Louvain Prison. (Those who encountered this story in book form would already have known that, since the preceding novel ends with his incarceration. But because Feuillade skipped Fantomas Under Arrest, this is the first we’ve heard of the arch-villain’s luck finally running out.) His men must be acting on their own using the master’s techniques.

Still, Juve is as certain as Fandor that they’ve not heard the last of their old nemesis. In fact, the detective considers it only a matter of time before Fantomas outwits his captors and escapes. Fuck the Belgians and their life sentences— a proper French guillotine is the only way of dealing with the likes of Fantomas. With that in mind, Juve embarks on an undertaking that I can describe only as toweringly stupid. He goes to Louvain Prison with two of his subordinates on a mission to bust the fiend loose, so that they can then re-arrest him crossing the border back into France. The crime lord is carrying enough open indictments to send a whole army corps to the guillotine, so Juve and his partners wouldn’t even need to wait for him to commit any fresh illegalities. The plan is a resounding success with regard to springing Fantomas from his confinement, but since it leaves Juve locked up in his place, while Fantomas easily eludes the two other cops, the mission as a whole has to be counted a boondoggle.

Fantomas hides out in London for a while before returning to France via Nantes. At the train station, he ambushes a fellow traveler and helps himself to his identity. By a stroke of astonishing good luck, he happens to pick Judge Pradier— not merely an examining magistrate, but the very examining magistrate assigned by the judiciary to succeed Morel in Saint-Calais upon his pending retirement. That puts Fantomas in charge of the effort to catch his old accomplices, a position which he can exploit to reassert his authority over the gang. And as he acquaints himself with the Tergall couple and their case, Fantomas discovers an opportunity for a piggyback crime to double the already considerable haul. The marquise, it turns out, is cheating on her husband with the assistance of her maid (Suzanne Le Bret, of The Vampires)— who just happens to be Paulet’s girlfriend. Fantomas contrives to murder the marquis in a way that can easily be attributed to the philandering woman instead, and uses that leverage to blackmail her to the tune of half a million francs. Meanwhile, what he learns by questioning Paulet and Ribonard, in both official and unofficial capacities, convinces him that his former allies should best be reclassified as rivals, and duly eliminated. That’s about when Jerome Fandor arrives in Saint-Calais to launch an investigation of his own. And although this must surely be a mere coincidence, it’s also when Juve makes his move. Locked up he may be in a Belgian prison, but somehow or other the inspector has not been idle all this time, and he now begins making arrangements for his release and transportation to Saint-Calais as a material witness in the Tergall case. Obviously it’s all part of a trap for Fantomas, but trying to sort out how it’s supposed to work will only lead to brain injury.

Returning to the questions I raised at the beginning of the review, it seems likely that whatever the reason for stopping with five chapters, the decision to do so was made only after The False Magistrate was completed. Otherwise, why not skip all the way ahead and adapt The End of Fantomas, published in 1913, and therefore available for use when developmental work began on this picture? Also suggesting that The False Magistrate wasn’t consciously intended to close out the series is the ending, in which Fantomas makes yet another of his patented last-minute escapes. A comparison between the print and celluloid versions of Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine establishes that Feuillade wasn’t afraid to change a final outcome when it suited him, so fidelity to the source material can’t be the only explanation. And on top of everything else, The False Magistrate feels less like an ending than like a new beginning. Except for Paulet, none of the familiar supporting characters are present here: no Lady Beltham, no Princess Danidoff, no Josephine, no Nibet, not even Fandor’s rarely glimpsed boss at La Capitale or Juve’s more frequently seen one at the Security Service. The setting is new, too, Saint-Calais taking over from the familiar environs of Paris. And let us not forget that The False Magistrate begins with Fantomas in prison. Everything about that scenario says “start again” rather than “stop.” So perhaps there was an even more mundane motive for breaking off here than creator fatigue. Maybe The False Magistrate just didn’t make enough money to satisfy Gaumont with the start of World War I jacking up the price of nitrate-based chemicals (necessary to the production of film stock and explosives alike).

I’ve already mentioned the major reasons why fans of the series might well be displeased with The False Magistrate, maybe enough to do real harm to what we would now call the movie’s box-office performance. It just doesn’t deliver all that much of what its predecessors condition one to want in a Fantomas film. However, if you forget about Juve (which is easy to do, since he’s barely in most of the movie), The False Magistrate resolves itself into a fairly interesting glimpse at how a more “realistic” take on Fantomas— a Nolanverse Fantomas, if you will— might have worked in this era. Notice first that none of the people with whom Fantomas has to contend in Saint-Calais have ever met the man he’s impersonating. The imposture thus enjoys a kind of credibility that the preceding movies never achieved simply by invoking the criminal’s status as a master of disguise. Observe further how simple Fantomas’s methods are this time around: he gases the Marquis of Tergall to death with his own space heater, pulls away a ladder so that an inconvenient accomplice gets battered to death inside the church bell where he was rooting around for a parcel of hidden loot, garrotes the real Judge Pradier when and where no one is around to see it. That kind of thing could be effectively terrible in its own right if we weren’t already primed to expect killer pythons and cadaver-skin gloves. And for Fantomas to position himself as a regional law-enforcement official is still inventively dastardly enough to maintain his bona fides as more than an ordinary crook. The problem is simply that part five in a series is much too late to work this kind of basic tonal transformation on it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact