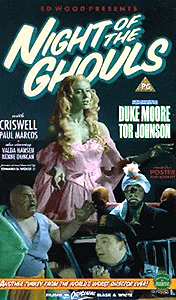

Night of the Ghouls / Revenge of the Dead (1958/1984) -***

Night of the Ghouls / Revenge of the Dead (1958/1984) -***

In between the completion of Plan 9 from Outer Space and its release most of a year later, Ed Wood got to work on his third and final straight horror film. (As always when discussing Wood, “straight” applies to intent only; the execution would be just slightly less twisted than usual.) A loose sequel to Bride of the Monster, Night of the Ghouls was an even more unapologetic throwback to the style of the 30’s and 40’s. Maybe that’s why Famous Monsters of Filmland went nuts over it, running a substantial promo piece in their issue for April of 1959. That old-timey spookery was Forest J. Ackerman’s first cinematic love, after all, and nobody was really doing it anymore in the late 50’s. Anyone who shared Ackerman’s enthusiasm after seeing the Famous Monsters pictorial was destined for disappointment, though. Although it may have received some manner of preview screening once or twice while Wood was putting the finishing touches on it, Night of the Ghouls never showed up in regular theaters that year, nor did it appear the next year, or the next, or the next. Indeed, Night of the Ghouls in its final, completed form would not be seen by anyone not involved in its creation until the mid-1980’s, when it was released to home video! As you might imagine, there’s a tale there.

Wood, it will not surprise anyone to hear, always had money troubles, in his professional life as much as his personal one. Night of the Ghouls, like all his movies, was shot on a “rob Peter to pay Paul” basis, but this time, Wood found himself fresh out of Peters when the last Paul came knocking. That final Paul was the post-production lab that Wood had hired to strike the exhibition prints, and when no money was forthcoming to pay for those prints, the lab impounded them along with Wood’s negative. Labs like that tend to be skittish about throwing things away (you never know when any particular deadbeat might scrape together the necessary cash, after all, and nobody likes a lawsuit), but every cubic inch of vault space devoted to storing some bum’s movie is one that can’t be given over to a paying customer instead. The way they resolve that conflict is by charging rent for film reels left in their custody. If Wood couldn’t afford to pay the lab in 1959, it’s no surprise that he continued being unable to pay as those rent charges drove the ransom for his movie ever upward, and Night of the Ghouls was still in that vault when Wood died in 1978. That’s where Wade Williams came in. Williams is an extremely minor producer/director, but a fairly major collector of antique sci-fi movies and the commercial rights to same. When he bought Plan 9 from Outer Space in 1982, Wood’s widow, Kathy, mentioned to him that there was this other, unreleased Ed Wood movie hidden away, just waiting for somebody to pay the lab fees on it. With that (and probably with a bit of negotiation between Williams and the lab to write off some of the accumulated rent), Night of the Ghouls was at last free to be seen by whatever public might still be found to care about it— a mere 26 years behind schedule.

You remember the old Willows house, on Willows Lake? The place where Dr. Eric Vornoff used to have his backyard-and-basement monster factory before he, it, and the giant octopus in the lake all went up in an inexplicable nuclear explosion that the neighbors were even more inexplicably untroubled about? Well, somebody has rebuilt the place— just don’t ask Ed Wood who, how, or to what purpose. Also, just forget about that mushroom cloud, and pretend the house burned down after being struck by lightning, okay? Anyway, it doesn’t really matter why the house is back up on its foundations. The important thing is that an old couple (Harvey B. Dunn, of Teenagers from Outer Space and The Sinister Urge, and Margaret Mason, from a bunch of inconsequential TV guest spots) had some car trouble in its vicinity tonight, and were attacked by a ghostly woman dressed all in white (Valda Hansen, from Norma and Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off). Curiously, the ghostly woman dressed all in white was herself attacked shortly thereafter by a ghostly woman dressed all in black (Jeannie Stevens, of Wood’s failed television pilot, Final Curtain), but Henry and Martha had the car restarted by then, and were miles down the road already. The spooked wayfarers rushed to the police station, where they’ve just finished telling their story to Inspector Robbins (John Carpenter— but not the one you’re thinking of— apparently stepping into Harvey Dunn’s Bride of the Monster role). Robbins in turn summons Lieutenant Daniel Bradford (Take It Out in Trade’s Duke Moore, who is not reprising his Plan 9 from Outer Space role, even though he might as well be) from his home.

Bradford is supposed to have the night off, and he’s rather irritated to receive the inspector’s call. Robbins has reasons for wanting him on the case specifically, however; evidently a lot of weird shit goes down in this precinct, although nobody likes to talk about it, and Bradford is the resident expert on weird shit. The lieutenant’s marching orders are to check out the Willows house, its grounds, and the nearby disused cemetery to see if anything, normal or paranormal, presents itself to explain the old couple’s experience. Of course, the police like to keep cases like this one quiet, so Bradford’s backup will have to be limited to a single patrolman. To the absolute horror of all concerned, the audience most definitely included, Robbins selects Kelton (Paul Marco) to be that patrolman. Perhaps you’ll recall Kelton. He was the cowardly twit who provided the noxious comic relief in both Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space. Kelton gets almost as much time on camera here as in his two previous outings combined, and I confidently predict that most viewers will be wishing all manner of foul misfortune upon him before Night of the Ghouls is through.

Due to Kelton’s cowardice-induced lollygagging, Bradford is forced to make his initial sweep of the Willows Lake area unaccompanied. He encounters neither the white ghost nor the black one, and he’s beginning to think the whole trip was a waste of effort by the time he gets around to casing the house itself. Once Bradford is inside, though, he discovers to his considerable surprise that the place is actually in use. The current occupant is a professed psychic medium who calls himself Dr. Acula (Kenne Duncan, from Revenge of the Virgins and The Astounding She-Monster). Yes, you read that right: Dr. Acula. Anyway, when Acula confronts Bradford about what the hell he’s doing letting himself into other people’s houses, the cop cagily stalls long enough to get some idea what his host’s game is, and to pose as somebody in search of spiritualistic guidance. Conveniently, Acula is holding a séance this very night for a pair of old codgers desperate to contact their deceased spouses. Playing along, Bradford witnesses one of the most staggering displays of bullshit interplanar communication in the annals of film, involving a telekinetic trumpet, a line-dancing sheet-ghost with a slide whistle, and other things I can’t even begin to describe. The white ghost puts in an appearance posing as the wife of one of the attendees, thereby implicitly confirming herself to be no ghost at all, but an accomplice of Acula’s. There’s a male fake, too (Tom Mason, Plan 9’s notorious Not Bela), pretending to be the second guest’s dead husband and popping out of a coffin to advise her on remarriage to Coleman Francis regular Tony Cardoza.

That’s about when Kelton finally shows up. No sooner does he arrive than he is visited by the black ghost, into whom he uselessly empties his revolver (which tells us that at least one of the spooks hanging around Willows Lake is for real). The commotion causes another accomplice to interrupt the séance, and while Acula is away looking into the gunshots outside, Bradford slips out through a secret door he noticed earlier to investigate the house more thoroughly. It’s actually some pretty astute detective work, by the standards of cops in Ed Wood movies. Unfortunately, he’s gone long enough for Acula to notice his absence, and in another most un-Woodian show of competence, the medium recognizes that he’s been found out. As it happens, though, Acula has an ace in his hand that he hasn’t yet played— Dr. Vornoff’s monstrous henchman, Lobo (Tor Johnson again), who miraculously survived the destruction of the original Willows house, and whom Acula brought on staff when he set up shop in the rebuilt version. Lobo soon has Bradford and Kelton alike under control, with instructions from Acula to kill both cops just as soon as the psychic can get rid of his regular customers. Dr. Acula’s victory is not nearly so complete as it currently looks, however, because there’s something he never realized about himself. The con artist really is a medium after all, at least in places where the boundary between this world and the next is thin enough, and it’s awfully thin in and around that old graveyard. Acula’s ostensibly bogus séances have raised more dead people than Eros’s resurrection ray ever did, all of them pissed off at the inconsiderate asshole who won’t let them get a decent eternity’s sleep.

Night of the Ghouls has some real surprises up its sleeve. Most immediately obvious is an improvement in the standard of the dialogue, which is remarkably free of Wood’s characteristic insane non-sequiturs. Other signs of advancement may be even more significant, though. By this point, Wood had acquired sufficient technical skill to make it apparent what he was trying to accomplish, and incredibly enough, the style he’s most conscientiously aping is that of Orson Welles. Mind you, I’m not saying his Welles impression is any good, but it is recognizably a Welles impression. The portentous multi-character voiceover narration, the frequent and nonlinear flashbacks, even some of the shot compositions— all are right out of Citizen Kane. It’s just that they’ve all been Woodified, so they come out artless and strange. Night of the Ghouls also demonstrates Wood’s growth as a filmmaker by containing an unprecedented number of honestly effective images. Take the flashback to the old couple’s encounter with the white ghost. Mostly it’s pretty laughable, but then comes this close-up on Valda Hansen’s long, tapering, talon-like hands, writhing their way through a succession of distinctly Lugosian gestures, and for just a moment, you might feel just a twinge of the creeps. Lobo’s reintroduction is even better, not just technically, but also in how it pays off on all the idle chatter about “the mad doctor and his monsters.” The most effective bit of all, though, is the opening shot of the ridiculous séance. Truth be told, it’s kind of ridiculous, too, but it works. Dr. Acula in his turban sits at the head of a long, narrow table, on a throne adorned with human skulls. In front of him is a crystal ball with yet another skull inside it. As the camera pulls back, we see Acula’s customers seated along the edge of the table to his right, while to his left sit a row of skeletons, equal in number to the living participants. Something about the image goes beyond weird and goofy, all the way around to unsettlingly surreal before Acula opens his mouth and blows the mood. There’s enough of this stuff that if we didn’t have Kelton to contend with, and if Criswell and his fellow voiceovers would shut the hell up and let the screen speak for itself, Night of the Ghouls might be thought of in the same category as Daughter of Horror, as a ragged but worthy experiment in cinematic dream-logic.

One of the movie’s better nightmare images is so irrational that it simply can’t be fitted into the context of the story at all. While Bradford is poking around the house on his own, he comes upon an area that couldn’t possibly be part of it, architecturally speaking. Ascending a long, metallic spiral staircase, he discovers a storeroom full of theatrical props and costumes, which include a female mannequin that comes alive after he examines it for a moment. The reason this sequence so clearly doesn’t belong is that it was shot for a completely different project, 1957’s Final Curtain. Originally the pilot episode for a “Twilight Zone”-like anthology series (but made two years before there was such a thing as “The Twilight Zone”), Final Curtain was later to have become the opening segment of an anthology film called Portraits in Terror, but the TV show was not picked up for production, and the movie was never finished. Nor is Final Curtain the only stillborn Wood project partially preserved in Night of the Ghouls. A bewildering sequence unconnected to the main plot, featuring two juvenile delinquents brawling in the mud outside a juke joint, came from his uncompleted youth-crime melodrama, Rock and Roll Hell. And perhaps understandably, characters named Dr. Acula, had been wandering into and out of Wood’s work since practically the day he met Bela Lugosi. Most notably, Dr. Vornoff had been called “Dr. Acula” in an early draft of Bride of the Monster’s screenplay, and a different Dr. Acula would have been the title role in another abandoned TV series, this one planned to star Lugosi as a paranormal investigator rather like Seabury Quinn’s pulp hero, Jules de Grandin. Night of the Ghouls runs only 69 minutes, so all that extraneous material renders it incoherent even in comparison to other Ed Wood movies, sharply counteracting the improvements already noted.

Of course, Ed Wood didn’t gain what fans he has today by being good, so for many viewers, that incoherence will be a point in its favor. Less positive is the impact of a brand new tic, a maddening refusal to let a scene play out to any logical stopping point. For much of the film, there are three concurrent venues of action: wherever Bradford is, wherever Kelton is, and the two men’s police precinct. Switching among them frequently could have been an easy way to generate suspense. Have a look at C.H.U.D. for an illustration of the principle used correctly. But the success of that tactic depends largely upon knowing when to shift perspective, and in Night of the Ghouls, Wood doesn’t get it right a single, solitary time. Instead of building suspense, the constant locus-toggling has a disruptive effect akin to that of an injudiciously inserted commercial break. It harms our engagement with the story, and compounds our exasperation at having to spend time with Patrolman Kelton. Worse still, it creates openings for Night of the Ghouls to become boring from time to time, which is just about the one sin I’ve never seen an Ed Wood movie commit before. It’s still well worth a look just to see Wood displaying capabilities you never knew he had, but don’t expect quite the same level of Bizarro World filmmaking that his work usually delivers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact