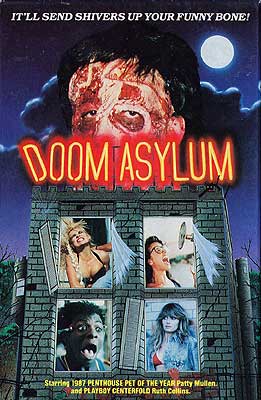

Doom Asylum (1987) -*˝

Doom Asylum (1987) -*˝

There’s a distinctive sinking feeling that I often get while watching a cheap horror movie made primarily for the home video market between roughly 1987 and 1998. It usually sets in toward the end of act one, when the villain or monster or whatever agent of horror the film has first makes its presence felt among the protagonists. “Oh no,” I suddenly find myself thinking, “Is this supposed to be funny?” It’s both the evil twin and the idiot brother to that wonderful rush of disorientation that washed over me when I first watched the fight between Ash and his own demonically possessed right hand in Evil Dead II. Doom Asylum, remarkably, didn’t even wait for the villain to be formally introduced before springing it on me. Its two factions of potential victims themselves form such a bizarre assemblage of overwrought caricatures that only the poor quality of the writing as a whole makes it possible to consider taking them seriously at first. After all, you could arrive at characters 70% as ludicrous just by sucking as much as screenwriters Richard Friedman, Rick Marx, and Steven G. Menken unmistakably do, so the joke isn’t obvious until that last 30% comes into play.

Like many slasher movies, Doom Asylum starts by setting up the killer’s origin. Scumbag lawyer Mitch Hansen (Michael Rogen, in a somewhat more substantial role than he played in Basket Case 2) has just won a lucrative and thoroughly corrupt lawsuit. The details are left vague, but the plaintiff was Hansen’s mistress, Judy La Rue (Frankenhooker’s Patty Mullen), the defendant was her rich husband, and the victors plan to split the $5 million take and run away to Palm Beach together, packing off “that brat” of Judy’s to boarding school so that she doesn’t spoil the couple’s fun. But while dividing his attention between Judy’s lips and the road in front of him, Mitch loses control of his huge Pontiac convertible, and runs it out of his lane into either an oncoming van or something else much sturdier than it. (Hey, you don’t expect them to show the actual wreck, do you? Car crashes cost money, you know!) The amorous conspirators are thrown from the vehicle, getting pretty badly banged up upon landing. Judy is partially dismembered, while Mitch leaves most of his face on the pavement. Both are pronounced dead at the scene. That verdict is premature in Hansen’s case, however, and Mitch regains consciousness just as the pathologists at the hospital where he was taken (inexplicably revealed later to be a mental hospital!) are beginning their autopsy on him. Hansen goes berserk once he realizes what happened, and stabs the two coroners (co-writer/producer Menken and Harvey Keith, the latter of Shrunken Heads) to death with their own dissecting tools.

Ten years later, on the same stretch of road where Mitch and Judy wiped out, a quintet of young doofi are following in their footsteps, even to the extent of listening to the same lousy cover of “House of the Rising Sun” on the radio. Curiously, one of them is Kiki La Rue (also Patty Mullen), the daughter whom Judy was fantasizing about sidelining shortly before the crash. Even more curiously, the kids’ destination is the ruin of the very loony bin where Judy and Mitch were taken by the paramedics. Kiki herself may or may not understand the latter connection, although she plainly does know that her mother died somewhere around here. If she does know that the old asylum was the site of Mom’s autopsy, too, then that might explain why she and her friends have chosen it of all places as the venue for a pizza picnic, even though it’s reputed to be the headquarters of a serial killer— and even though at least two members of the party, Darnell (Harrison White, later of KillHer and Resurrected) and Dennis (Kenny L. Price), fully believe the legend. The film itself never says one way or the other, but considering that a friend of mine and I once broke into the supposedly haunted ruins of a decommissioned water treatment plant for no fucking reason at all, I shouldn’t really complain about the lack of explicit motivation. Then again, neither my friend nor I really believed that we’d encounter anything worse in that huge concrete labyrinth than a few rats, which is not the case with this bunch.

In point of fact, each one of these kids plainly has something wrong with them, even without reference to “Let’s have a picnic in the Murder Ruins!” It’s only to be expected that Kiki remains troubled by her mother’s death, but something else again for her to reply, “Can I call you ‘Mom’?” when her boyfriend, Mike (William Kay), says to her, at the scene of the fatal wreck, “I’m not your mother, and I never could be. But I can try…” (She means it, too, never calling Mike by his proper name again!) As for Mike, he’s so pathologically indecisive that he can’t so much as offer to stop the car for Kiki at the crash site without second-guessing himself. Dennis, meanwhile, is so obsessive a baseball card nerd that he will eventually try using the gems of his collection to bribe his way out of being stabbed. Kiki’s best gal-pal, Jane (Kristin Davis), is also obsessed, but her fixation is on the psychology that she’s studying in high school or college or grad school or whatever. (For some reason, I find it abnormally difficult to discern just how much younger than their actual ages these folks are supposed to be.) She sees everything that everyone does or says through a psychotherapeutic lens— although her companions undeniably are tempting targets for such analysis. And Darnell? He’s just a troublemaking horndog, which makes him far and away the most well adjusted member of the ensemble.

Kiki and her friends are surprised to find that they’re not the only ones to think of trespassing on the asylum grounds today. A post-punk noise rock band called Tina and the Tots are already on the premises when the picnickers arrive, rehearsing loudly. (The song we hear them playing is actually “Tormental,” by Psychodrama.) Evidently Darnell has dealt with this bunch before, although I’m genuinely not sure whether we’re meant to take it figuratively or literally when he explains that they “play the local sewers.” In any case, he volunteers to deal with Tina and the Tots now by sneaking into the asylum and cutting the switch on the electrical junction box powering their amps and instruments. The three musicians’ responses to this intrusion are each very different. Drummer Rapunzel (the stylishly mononymic Farin) is lovestruck— or at least luststruck— immediately upon laying eyes on Darnell. (The feeling is more or less mutual, too, despite Darnell’s initial antagonism.) Communist keyboardist Godiva (Dawn Alvan) is annoyed to have five representatives of the petty bourgeoisie barging in on the band’s activities, but seems to regard their presence as having dispelled whatever vibe is necessary for her to make music satisfactorily, so that it isn’t really worth trying to do anything about them. Deranged lead singer Tina (Ruth Collins, from Prime Evil and Psychos in Love), however, treats the interruption of band practice as an act of war, and determines to respond in kind. Consequently, each side in this clumsily trumped-up conflict will have someone at whom to misdirect the blame at first when the stories of a homicidal maniac stalking the asylum prove to be essentially true. The only significant difference between legend and reality is that the killer, despite his choice of weapons, is no mad ex-coroner, but rather our old buddy Mitch Hansen. Naturally that means complications are bound to arise once Mitch gets a good look at Kiki while picking off her companions and their enemies.

Doom Asylum is so excruciatingly stupid and tedious that not even Patty Mullen can redeem it. Those who have seen Frankenhooker will understand at once how damning that is. Worse yet, although she’s nominally the star of the film, Mullen gets so little to do that she barely makes an impression, beyond that she spends most of the running time traipsing around in 1987’s idea of an exceedingly skimpy bikini. This despite playing a girl so fucked up that she takes her boyfriend literally when he proposes to do everything he can to replace the support she once got from her deceased mother! And of course it follows naturally that the rest of the cast is no better, although Ruth Collins does at least manage to be bad in a memorable and occasionally engaging way. I would not previously have guessed that it was possible to be the poor man’s Linnea Quigley, but that seems to be just what Collins was aspiring to with her performance here. Director/co-writer Richard Friedman makes no discernable effort at suspense, and while the gore effects are decent enough, they’re all presented in a flat, unimaginative way that robs them of whatever impact they might have made. The humor is half sub-Troma buffoonery and half surreal absurdism, with neither mode ever really landing. And it should probably go without saying that story logic was quite simply never a consideration, any more than it usually was in horror comedies of this witless stratum. The most truly baffling element of Doom Asylum, however, is the stock footage. Evidently Mitch Hansen passes most of the time when he isn’t actively stalking and slashing by watching old Todd Slaughter movies on TV. It feels like it’s supposed to mean something, but damned if I could tell you what. Regardless of the intent, the upshot is that Doom Asylum comes by a startling percentage of its second- and third-act running time by recycling random-ass clips from The Face at the Window, Murder in the Red Barn, The Crimes of Stephen Hawke, Never Too Late to Mend, and The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. All that said, there was one thing that made me forgive Doom Asylum just a little: for a while during the endgame, it looks like Tina might somehow usurp Kiki’s foreordained position as Final Girl, and although the filmmakers couldn’t bring themselves to throw that sharp a curve in the end, the size and nature of Tina’s role in the story remains a significant abrogation of the subgenre rules that Doom Asylum otherwise follows with robotic predictability.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact