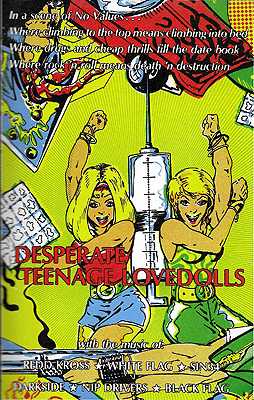

Desperate Teenage Lovedolls (1984) -**

Desperate Teenage Lovedolls (1984) -**

Given my virtually lifelong involvement with punk rock, it was probably inevitable that I’d get around to reviewing a punk rock movie sooner or later. Why I picked Desperate Teenage Lovedolls, which Dave Markey made in collaboration with the McDonald brothers of Red Cross/Redd Kross, over Penelope Spheeris’s more obvious (and much better) Suburbia, I have no idea. It’s probably just because it was there, and so was I. On the other hand, I’m kind of glad I did, because Desperate Teenage Lovedolls, by its very existence, encapsulates the most life-affirming aspect of punk ideology in a way that Suburbia does not.

The story is really simple, though not altogether credible. A teenage girl named Kitty Carryall (Jennifer Schwartz) has dreamed of being a rock star since before she can remember. She and her friend Bunny Tremolo (Hilary Rubens) have been playing guitar together in Kitty’s basement for months, writing songs and fucking around, but you can’t really call their project a band. They’re just a couple of girls with a pair of Gibsons. Then one day, a friend of theirs named Alexandria (the enigmatic Pilkington) breaks out of the mental hospital to which her parents have committed her for no really good reason, and comes to hide out in Kitty’s bedroom. Conveniently enough, this happens right after a particularly fierce fight between Kitty and her mom (note that Kitty’s mom and Alexandria’s psychiatrist are both played by the same teenage boy!), and Kitty, Bunny, and Alexandria all decide to run away from home together. Alexandria drops out of the picture quite rapidly, becoming a junkie and severing all ties to her fellow runaways. The remaining two girls wander the streets of Los Angeles committing petty crimes for pocket money until finally they steal an acoustic guitar from another street kid, and become annoying street musicians.

Kitty and Bunny are still looking to make names for themselves in the music scene, though, and so they set about looking for a drummer. They roam all over town putting up flyers, an activity that leads directly to two very unpleasant developments. First, their flyering in front of a Venice Beach video arcade earns them the enmity of an all-girl gang called the She-Devils, who consider the arcade their turf, and who have inexplicably mistaken the Lovedolls (the band-name Kitty and Bunny have chosen) for a rival gang. Secondly, while Kitty is out sticking flyers under the windshield wipers of parked cars, she stumbles upon her mother, who has spent the months since Kitty ran away looking for her all over the city. Kitty’s mom chases her across the park where they ran into each other, right into the middle of a group of homeless punk kids, who in their eagerness to defend one of “their own” from a seemingly hostile adult, end up killing Kitty’s mom. Kitty doesn’t really seem to mind, though, partly because she never got along with her mother anyway, but mainly because one of the street kids, a girl named Patch (Janet Housden), turns out to be a drummer! With Patch on hand to complete the lineup, the Lovedolls are a band at last!

The girls’ rise to stardom is preposterously meteoric. One of Kitty and Bunny’s street “performances” attracts the attention of a smarmy A&R man from Capitol Records, by the name of Johnny Tremayne (Steve McDonald). Tremayne promises to make big stars of the Lovedolls, and he is as good as his word (though Bunny must pay with her body for Tremayne’s benefice). Soon, they’re the biggest names in the L.A. punk scene, enjoying huge crossover success as well in the mainstream market. (Do I detect a little wish-fulfillment here, Redd Kross?) Eventually, the girls decide that Tremayne has outlived his usefulness, and that the time has come to pay him back for his exploitation of Bunny. Kitty and Bunny attend a party at Tremayne’s place, and spike his wine glass with an entire vial-full of liquid LSD. Johnny starts freaking out right after the Lovedolls leave, finally becoming a living cliche by leaping to his death from the roof of his apartment building, convinced that he can fly. If the now manager-less Lovedolls’ continued success is any indication, they were right about not needing the record-company sleazebag anymore.

But the Lovedolls’ time in the sun (like the movie itself) is short, and it isn’t long before the band is on the way down. First, the She-Devils make their move, attempting to stab Kitty while she strums her guitar alone on the beach. The assassination attempt backfires, though, when Kitty gets the knife away from the gang’s leader, and stabs her with it instead. Kitty takes advantage of the surviving She-Devils’ shock at their chief’s death to make her escape. But those gangster chicks aren’t so easily beaten, and they continue to follow the Lovedolls’ movements around the city, until they finally work up the nerve to take their revenge. They jump Kitty and Bunny in a park, this time armed with guns rather than switchblades, and succeed in killing Bunny. Kitty shoots the She-Devils’ new leader in return, and as the rest of the gang flees, turns the gun on herself. Just Kitty’s luck there had only been two bullets in the cylinder. With Bunny dead, the Lovedolls are no more, and Kitty winds up a drunken bum on the streets of Los Angeles, forgotten by everyone but a guitar-strumming Hare Krishna who tries to sell her a flower just moments before the closing credits.

By any objective standard, Desperate Teenage Lovedolls is an incredibly bad film. Had this movie been made by even the lowliest fly-by-night studio, it would have been lucky to get even half a star from me. But— and this is the single most important thing about Desperate Teenage Lovedolls— rather than being made by any kind of studio at all, it was made a bunch of L.A. punk rockers, using the exact same strategy that produced the bulk of their music. In much the same way that the guys from Red Cross/Redd Kross got together one day and said, “okay, we’re a band now— let’s write some goddamn songs,” Markey and his friends somehow got it into their heads that they were going to make a movie, and just fucking did it. They got a Super-8 camera from somewhere, cobbled together something that resembled a script using wildly exaggerated versions of their own life experiences, and went out into the streets to bring this impossible project to fruition. They scored the film with their own music, and with other songs taken from their record collections, and kept pestering friends of friends of friends until they found someone who had access to the editing equipment they would need to make a semi-coherent movie out of all their footage. And finally, against all odds, they even found a way to distribute the goddamned thing! All in all, the whole project must have cost about $300. So as awful as it is, Desperate Teenage Lovedolls has one form of enduring merit. It’s the D.I.Y. ethic of punk rock translated into film— “You can make a movie,” Desperate Teenage Lovedolls says, “even if you actually can’t.”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact