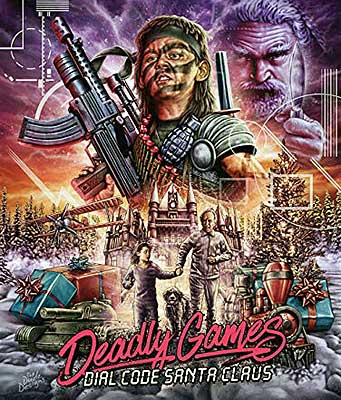

Deadly Games / Deadly Games: Dial Code Santa Claus / Dial Code Santa Claus / Game Over / 36:15 Code Father Christmas / 3615 Code Pere Noël (1989) ***½

Deadly Games / Deadly Games: Dial Code Santa Claus / Dial Code Santa Claus / Game Over / 36:15 Code Father Christmas / 3615 Code Pere Noël (1989) ***½

In France, there used to be a thing called Minitel. The name was a contraction of “Médium Interactif per Numénation d’Information Téléphonique” (“Interactive Medium for Digitizing Telephonic Information”), and as originally conceived in 1978, the system was supposed to be little more than an electronic replacement for printed directories of street addresses and telephone numbers, accessible via telephone itself— sort of a suped-up version of the North American 411 directory assistance lines. But by the time the first dedicated Minitel terminals became available two years later, the service was already recognizably evolving into a parallel to the early, text-only internet of listservs and BBSes. Minitel subscribers could use it to exchange e-mail or text-chat messages; to buy bus, train, and airline tickets; to receive news bulletins; and to do quite a few other surprising things. There were even Minitel dating networks and “type dirty to me” businesses analogous to the phone sex lines that started appearing in the US at the turn of the 90’s. The French government treated Mintel as a utility, even to the extent of having coin-operated public kiosks set up in urban areas, just like pay telephone booths. Home terminals could usually be had for free (they officially remained the property of the relevant government agency, on loan to the customer), but use of the devices was billed by the minute in the manner of long-distance telephone calls. And because the whole thing ran over the nation’s phone lines, it was necessary to create a means of access intelligible to automated switchboards— specifically, a set of four-digit numerical codes to shunt Minitel queries out of the regular phone system. Those codes were organized along remarkably similar lines to the World Wide Web’s domain suffixes, and in much the same way as “.com” became by far the most important of the latter, the number to dial for most Minitel transactions was 3615.

In other words, when French audiences in 1989 encountered advertising for a movie called 3615 Code Pere Noël, they would have recognized at once that Minitel was going to be central to the plot, just as American audiences understood the telecom implications of titles like 976-EVIL and feardotcom. Abroad, though, that title was basically untranslatable, accounting for the varied array of export titles which this film has carried. I’ll be using Deadly Games mainly for concision’s sake— although it also has the advantage of being less misleading than Game Over while sounding less clunky than any of the attempts at a more faithful English rendering of the original handle. Whatever you want to call it, however, this is hands-down the most twisted Christmas movie I’ve seen in years. Although it sounds essentially similar in concept to Home Alone (indeed, writer/director René Manzor threatened to sue 20th Century Fox for plagiarism), Deadly Games is crucially different in tone. Its protagonist is basically a juvenile Bruce Wayne, able to draw on limitless wealth, genius-level intelligence, and a peerless knack for gadgeteering, along with the benefits that come with a strict self-imposed regimen of physical fitness training. The home-invading villain, meanwhile, is no mere burglar seeking to exploit the holiday travel plans of the affluent, but a psychotic killer in a Santa Claus suit. And despite the occasion flirtation with slapstick and visual comedy even during moments of high tension, Deadly Games is deadly serious about the stakes of the confrontation between the two characters.

Ten-year-old Thomas de Frémont (Alain Lalanne) is the heir to the Au Printemps upscale department store empire. He’s a technological polymath with an off-the-charts IQ, but he’s still a little kid— and in some ways, he’s even a bit immature for his age. He plays dress-up and make-believe games with the same relish as any other child (albeit with considerably higher production values); he’s devoted to his ancient, diabetes-enfeebled grandfather (Louis Ducreux); and he’s enough of a mama’s boy that his widowed mother (Brigitte Fossey) feels constrained to keep her budding romance with her personal assistant, Roland (François-Eric Gendron), on the downlow. And unlike his best friend, Pilou (Stephane Legros), Thomas still wholeheartedly believes in Father Christmas. This December, he’s been spending a lot of time on the Minitel chat site, 3615 Pere Noël, and he’s unshakably convinced that the messages he receives over the modem in his basement computer lab really are coming from the immortal fat man at the North Pole.

In fact, however, Thomas’s Minitel interlocutor is a crazy guy (The Murders in the Rue Morgue’s Patrick Floersheim) with a thing for children. I don’t think it’s supposed to be that kind of thing for children, mind you, but I wouldn’t rule it out, either. The first time we see him, he’s trying to join the neighborhood kids in a snowball fight, becoming absolutely crestfallen when his intended playmates break up their game rather than let him participate. The dude just has a vibe, you know? Evidently that vibe is harder for adults to pick up on, though, because Roland feels no qualms about hiring the big weirdo as a last-minute addition to Au Printemps’s round-the-clock army of in-store Pere Noëls. In a roundabout way, that gig is what makes the loony a danger to Thomas de Frémont, because their Minitel chats have exposed enough personal information to link the boy to the directorate of the department store. When an altercation with an unusually obnoxious lap-sitter gets the crazoid fired just hours before closing time on Christmas Eve, he overhears Roland talking to the shipping department about delivering Thomas’s Christmas presents while waiting for his pink slip. That gives him an idea. Instead of enduring the ritual humiliation of a formal dismissal, the newly dethroned store Santa skulks out of the office with Roland still on the phone, sneaks down to the basement garage to waylay the delivery driver, and takes his victim’s place at the wheel of the truck carrying the Frémont kid’s gifts, still clad in his fur-trimmed Saint Nick finery.

This, meanwhile, is the situation into which the counterfeit Claus will be intruding himself at the Frémont mansion. Mom, workaholic that she is, is still at Au Printemps, personally orchestrating the climax to the retail year. Papy, who needs his grandson’s guardianship much more than the boy needs his, has gotten thoroughly tuckered out playing Dungeons & Dragons, and has finally won Thomas’s assent to go to bed. Thomas, for his part, is running a final round of tests on his preparations to do something that no other child has ever accomplished: to capture incontrovertible evidence that Father Christmas really does exist. He’s got all the mansion’s security cameras rigged for recording on the VCR in his computer lab, their feeds controlled from a wrist-mounted monitor gizmo of his own design. The bulletproof shutters on all the windows and exterior doors are similarly modified for remote control, so that Santa will be able to escape only by retreating back up the chimney that admitted him in the first place. And Thomas himself is lying in wait beneath a table in the parlor, on which is laid out the traditional offering of midnight snacks for Pere Noël. Thus when the Minitel Maniac arrives with his truckload of toys, and finds every normal means of ingress blocked, he makes his final commitment to the bit by scaling the exterior of the mansion, and rappelling down the chimney into Thomas’s ambuscade.

At first, Thomas is over the moon at his success. That’s him! That’s Santa Claus, and Thomas is getting his visit to the Frémont house on tape! The kid’s dog, J.R., has a truer understanding of the situation, however. J.R. treats the chimney-stinking stranger the same as any other intruder, leaving the man little choice but to do something about him. There’s a saw-like bread knife on the table with the Santa snacks, and the lunatic grabs it to make short work indeed of the dog. Thomas is unable to control his terrified screaming as Father Christmas butchers his pet, and thereby draws the home-invader’s attention to himself. From this point out, the boy who still believes in Santa Claus will have to spend the wee hours of Christmas morning fighting him for his and his grandfather’s lives.

There’s one more thing you need to understand in order to get how brilliantly sick and wrong Deadly Games really is. At the start of his vigil, Thomas gets a goodnight phone call from his mother. When he explains what he’s doing, she warns, “You mustn’t try to see Santa, or he’ll get angry and turn into an ogre.” All she’s trying to do is to nudge the boy into going the fuck to sleep, relying on the kind of magical child-logic that she knows he’ll respond to, but the unintended result is to furnish him with an explanation for what happens after J.R. attacks the Santa-suited prowler. Throughout the rest of the film, Thomas remains as convinced as he ever was that the man who came down his chimney truly is Father Christmas! When he goes to retaliatory war, booby-trapping the house with increasingly lethal devices improvised from his toys and games, Thomas is under the impression that he’s fighting the real Santa Claus, and believes himself to be at fault for unleashing the personification of Yuletide joy’s evil side. Nor does René Manzor flinch in the slightest from the psychological implications when Thomas and Papy win the only kind of victory that was ever really available to them.

I can understand why Deadly Games didn’t get more exposure outside of its home country, even without considering the possibility of 20th Century Fox springing frivolous but expensive lawsuits on would-be distributors in retaliation for Manzor’s own threatened litigation. The film is just absolute tonal whiplash from beginning to end! The opening scene of the maniac being snubbed by all the kids in his neighborhood alludes on the one hand to Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer’s fawnhood shunning, while raising the ominous specter of child molestation on the other. The heavy-handed pathos hinted at when the subject of Thomas’s dead father arises at breakfast a bit later is in line with the maudlin mood that threads itself through most Christmas movies at some point or other, as is Roland’s visible hurt over the secrecy with which Louise de Frémont approaches their relationship when her son is around to notice it. But those scenes follow the most overtly comic sequence in the film, as Thomas’s routine of early-morning calisthenics takes the form of a nearly shot-for-shot parody of John Rambo’s preparations for battle in Rambo: First Blood, Part II, set to a just-short-of-actionable copy of Survivor’s “The Eye of the Tiger.” And then of course there’s the utterly bent primary spectacle of a ten-year-old boy locked in mortal combat against a maniacal Santa Claus— which grows yet more seriously bent as it gradually becomes apparent that the killer understands himself to be playing with the child he’s trying to murder. Throw in a full-bore 70’s bummer ending, and there’s barely an emotional state that Manzor doesn’t try to provoke at least briefly. Even without Home Alone to provide a normal, mainstream counterexample of this premise, Deadly Games would be pretty fucked up.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact