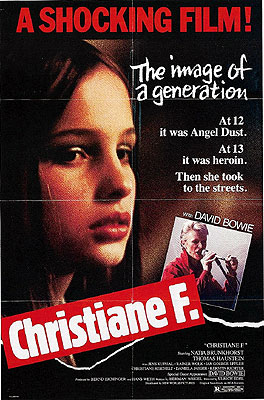

Christiane F. / We Children of the Banhoff Zoo / Zoo / Christiane F.: Wir Kinder vom Bahnhoff Zoo (1981) ***

Christiane F. / We Children of the Banhoff Zoo / Zoo / Christiane F.: Wir Kinder vom Bahnhoff Zoo (1981) ***

If there’s a dumber thing to do to yourself than heroin, I can’t imagine what it would be. I don’t say that as an all-around foe of recreational drug use, either. Taken intelligently and with discrimination, drugs can facilitate social bonding, spark creativity, boost energy and productivity, alleviate stress, enhance the enjoyment of other pleasures, and even lead one to insights about oneself and one’s life. There are risks involved, obviously, and some drugs are more dangerous than others, but most mood-altering, mind-altering, or metabolism-altering chemicals have some kind of upside somewhere. Heroin, though? I’ve never heard a happy heroin story. Best-case scenario, you stop using it before it kills you, and then spend the rest of your life trying to regain the trust and affection of all the people you fucked over while you were in its thrall. And what’s more, I have yet to meet a heroin user who didn’t know that, or who expected their case somehow to be an exception to the rule. So why does anyone do it? The best explanation I’ve heard was the one offered by John Lydon in The Filth and the Fury, when he was discussing the bad end to which Sid Vicious came: heroin is self-pity in chemical form. I’ve never been a junkie, but I’ve known enough of them to recognize that hardly anyone turns to smack unless their lives are already ruined beyond their ability to envision a means of repair. So when we encounter the phrase “heroin epidemic,” the first question we should ask is, what’s producing so much despair that enough people to constitute an epidemic are being driven to slow-motion suicide?

The issue was fairly acute in Europe during the mid-to-late 1970’s; the whole western half of the continent was experiencing a heroin boom unprecedented in its history, although the severity of the problem was not widely recognized until the following decade. The supply side of the equation was well-studied, and is reasonably well understood. For one thing, the end of the Vietnam War deprived East Asian heroin producers of a lucrative market, as the GIs (who had as fair a reason for craving oblivion as anybody) went home and took thousands of addictions with them. The dope-pushers of Indochina would reconnect with their lost customers eventually, but in the meantime it was easier to break into Europe by shipping through Indonesia to Amsterdam. Meanwhile, the West German economy’s voracious appetite for low-skilled, foreign “guest workers,” mostly of Turkish extraction, created a channel through which Afghan poppy-growers could peddle their wares to Europeans as well. The demand side is harder to pin down, however. Lev Tolstoy’s observation that unhappy families are each unhappy in their own unique ways is probably true of unhappy populations as well, but if you’re interested in Berlin’s 70’s smack problem specifically, one good place to start would be a book entitled Christiane F.: We Kids of the Bahnhof Zoo.

Christiane F. was in effect the ghostwritten memoir of Christiane Felschinerow, a teenager whom journalists Kai Hermann and Horst Rieck met while they were covering the trial of a man who traded heroin for sex with underage girls. What started off as a single two-hour interview became two months’ worth of tape-recorded reminiscence about life among the adolescent junkies of West Berlin. Those sessions gave rise first to a series of articles in the national news magazine Stern (“Star”), and then to the book in 1979. Christiane F. was an international sensation (it even appeared in the US in 1982), which inevitably made it a target for adaptation to film or television. It ended up getting the full cinematic treatment, and the film version was at least as successful as the book. Despite its lurid and salacious subject matter, the movie is not so much sleazy as unflinching. It’s a serious-minded picture that seeks to present as complete an illustration of West Berlin’s late-70’s drug scene as possible, allowing Felschinerow’s experiences to speak for themselves without interference from adult moralizing. Naturally, that means it’s uncomfortable viewing for those who’d prefer an unequivocal, Mr. Mackeyian “Drugs are bad, m’kay?”

If thirteen-year-old Christiane F. (Natja Brunckhorst) is in despair, she hides it well. Just the same, there are signs of serious stress in her life if you look in the right places. The neighborhood where she lives— a cluster of high-rise apartment towers called Gropiusstadt— is one of those mid-century “City of the Future” housing projects that were rotting into slumdom by the 1970’s, thanks to corner-cutting by the builders and municipal governments tending to use them to warehouse problem residents like deinstitutionalized psychiatric patients and the chronically unemployed. Christiane’s parents split up years ago, and her mother (Christiane Lechle) is too wrapped up with her new boyfriend, Klaus (Uwe Diderich), to give her children the attention they require. Also, although the movie doesn’t mention the abuse described in the book, it’s plain enough that Christiane harbors considerable resentment toward her absent father— enough to consider it a personal betrayal when her little sister decides to move out and go live with Dad.

We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that Christiane jumps at the temporary escape symbolized by Sound, the combination discotheque-arcade-movie theater where her best friend, Kessi (Daniela Jaeger), recently started hanging out. Strictly speaking, neither girl is old enough to get in, but age of admission is only sixteen, and it’s not like the club’s teenaged doormen give a shit. On Christiane’s first visit to Sound, she meets a pair of boys whose influence is destined to derail her whole life. Detlev (Thomas Haustein) and his roommate, Axel (Jens Kuphal), are the kind of guys that girls like Christiane always seem to fall for: hip, personable, worldly without being threatening, and just the slightest bit criminal. They live away from home in a fashionably skanky flat with a bunch of other dudes, unbeholden to parents, teachers, or adult authority figures of any kind. They shoplift and vandalize for fun. They even know where to score hash and valium, the drugs of choice for most of the city’s more adventuresome teens. But the most salient fact about Detlev and Axel is that they’re junkies. Novice junkies, to be sure, and junkies who as yet are still masters of their vices, rather than the other way around, but junkies just the same.

Christiane is initially turned off by the discovery that her new friends smoke heroin, but the more she grows to like Detlev, the more curious she becomes. At the same time, an important moderating influence on her behavior is taken away when Kessi’s mother (Ellen Essen, of Harlis) decides that Christiane is leading her daughter into trouble, and forbids any further contact between the two girls. True, Kessi’s mom has it exactly backwards— it’s Kessi who most often plays ringleader when she, Christiane, and the boys from Sound go out to make mischief. But Kessi has her head screwed on much tighter than Christiane, Detlev, or Axel, so the trouble the other three kids get into without her is apt to be much more serious. Kessi, one suspects, would have talked Christiane down when she finally got it into her head to try heroin for herself, following a David Bowie concert which she attends with an addict much further along in dissolution than either Axel or Detlev.

Soon after taking her plunge into the deep end of recreational doping, Christiane learns about the Bahnhof Zoo, the dilapidated train station near the Zoological Gardens that forms the hub of West Berlin’s junkie subculture. The Bahnhof Zoo is the easiest place to score, for one thing, and its bathrooms are such a freak show of youth degeneracy that nobody bats an eyelash if you want to shoot up in the stalls. The station is important on the other side of West Berlin’s dope economy, too, because it’s where junkies of both sexes gather to turn tricks in order to finance their next hit. It throws Christiane for a loop to imagine her boyfriend (as we may safely consider Detlev by this point) jerking off men twice his age in the front seats of their cars, but drugs cost money, and well-heeled closet cases are a reliable source of that. Besides, it beats working. And since Christiane celebrates her fourteenth birthday by graduating from smoking her heroin to mainlining it, it’s only to be expected that her first shift at the Bahnhof Zoo Blowjob Bazaar isn’t far in the future.

There’s an extent beyond which once you’ve seen one junkie flick, you’ve pretty much seen them all. The Stations of the Needle aren’t always presented in the same order, and it’s even permissible to skip one or two of them, but you can generally count on: a wakeup call of a nonfatal overdose, a grueling and nightmarish attempt to kick cold turkey, a relapse into addiction at the earliest subsequent opportunity, the deaths of one or more of the protagonist’s fellow dope fiends, and a downward spiral of degradation as the viewpoint character abandons one scruple after another in pursuit of the next fix. Christiane F. checks all those boxes, plus the optional one at the end where the junkie gets clean and starts putting her life back together. In that respect, the film ends a good bit more happily than Christiane Felschinerow’s real life seems likely to; now in her 50’s, the former poster girl for West Berlin’s dope crisis is dying slowly of hepatitis C after decades of on-again, off-again drug abuse.

Christiane F. has been mired in controversy since the day it premiered, reviled by detractors who claim that it glamorizes heroin addiction. I must admit I see their point. As played by Natja Brunckhorst, Christiane is pretty, stylish, increasingly self-assured, and above all a survivor. She’s exactly the character you would write if you wanted someone who’d read as sophisticated in the eyes of naïve teenagers. That portrayal is rather at odds with any notion of Christiane F. as a sort of cinematic Scared Straight program. It’s also a questionable choice for a movie in search of the raw truth about heroin addiction to feature a personal appearance by David Bowie, then arguably the world’s most successful and beloved drug fiend (although, to be fair, Bowie was mainly a cocaine guy during his druggie years). Just the same, it isn’t as though Christiane F. ever glosses over the hardships that Christiane causes herself, or leaves any room to doubt that it was just dumb luck that let her live to shoot up another day while her friends died like roaches all around her. Consider the withdrawal sequence that forms the thematic centerpiece of the film. Having been discovered in mid-overdose by her mother and Klaus, Christiane is locked in her bedroom with Detlev so that the young lovers can support each other on their shared journey through Detox Hell. For days, they sweat and shiver and ache and vomit and suffer side by side, flaring their tempers at each other as if what each of them was going through were somehow the other’s fault. In the end, they emerge clean and healthy, and ever so proud of their hard-won achievement. They hurry to the Bahnhof Zoo to tell all their friends of their triumph… and not fifteen minutes later, they’re back in those squalid toilets, shooting up again. All that pain, all that sickness, all that misery, and they toss away the prize that made it worthwhile at the first chance they get. This movie might make heroin addiction look glamorous to a certain specific mindset, but it sure as hell doesn’t make it look fun.

I’m not sure it answers the big question, either, which is maybe a point in its favor. The thing that reads truest about Christiane F. is that there’s no sign of peer pressure as one usually understands it. At no point does anybody think it’s a good idea for Christiane to take up heroin. She starts off thinking of smack as the one drug that is never okay, and nobody ever tells her different. Indeed, every one of her friends insists that she stands to gain nothing from cultivating the habit— even the ones who say so with a spoon in one hand and a cigarette lighter in the other. Christiane’s initial visit to Sound is nearly her last, thanks to a horrific encounter with a cadaverous junkie, nodded out on one of the toilets with a needle sticking out of his goddamned neck. When she first catches Detlev making a buy, his reaction is a kind of peevish shame. So why does she do it? We can see that Christiane is missing something from her life, and there are some clues here and there as to what it might be. Parental involvement is high on the list, of course, but Christiane’s attitude toward her father suggests that that isn’t necessarily something she wants, either. Her physical environment seems a fair suspect, too; one of the things trimmed as an unnecessary expense by the builders of Gropiusstadt was any kind of green space or area for recreation, and the complex is visibly no place to try to raise a child. But what stands out the most to me is that each major step in Christiane’s descent is preceded by a loss of some kind: her sister moving away, Kessi’s mother breaking up their friendship, an interruption in her relationship with Detlev, the death of a fellow junkie. The connection is never strong enough or clear enough to be dispositive, but again I think that’s a good thing here. There’s always some irreducible mystery when people kill themselves, whether they do it in one fell swoop or a little at a time.

Christiane F.’s most effective trick, though, is its casting. Very few of these people were actors, and the kids were all real teenagers. Those two factors do wonders for the film’s relatability, and keep it honest in a way that probably could not have been managed with a cast of older professionals. No matter what happens, sooner or later the youth and inexperience of Natja Brunckhorst, Thomas Haustein, and the rest wrench you back to face the reality that their performances represent. You don’t even need parental instincts to give Christiane F. a hand-hold on you. All it takes is the memory of some stupid-ass thing you did when you were young enough and foolish enough to think you were invincible, some bullet in your past that you dodged when you shouldn’t have been able to. If junkie movies are mostly the same, then it follows that each of them needs to try harder to justify itself as the one you should bother watching. Christiane F.’s bid for your attention is that it never lets you forget that this was somebody’s life, and that thousands more like it are limping toward the same end or worse even now.

This review is for Nick, who won’t ever get to read it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact