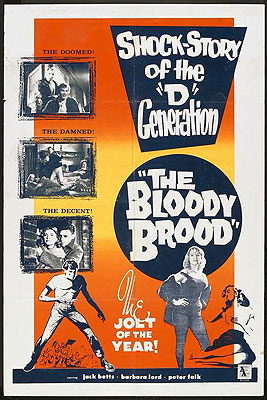

The Bloody Brood (1959) ***

The Bloody Brood (1959) ***

At no point in my lifetime have beatniks ever been more than a punchline. Effectively extinct before I was born, they had no way of defending themselves against being redefined in pop-culture as a bunch of navel-gazing, bongo-thumping layabouts, maundering foolishly in a slang so dense that it barely even qualified as English anymore, constructed so as to impart the illusion of deep thinking to puerile inanities than anyone would instantly recognize as such if they were couched in plainer language. Besides, who can do anything but laugh at a rebellion that adopts the turtleneck sweater as its most visible tribal emblem? Back in their 1950’s heyday, though, people were every bit as scared of beatniks as later generations would ever be of bikers, hippies, punks, or goths. And from the standpoint of a mainstream heavily invested in both communitarian conformity and reflexive respect for institutions, it was completely reasonable to be afraid. Although the beatniks were by no means America’s first counterculture, they arguably were the first to reject their parent society’s value system wholesale, instead of just objecting to this or that bit of it in detail. Beatniks permanently changed the terms of generational conflict, from the age-old model in which the youth are unable to meet their elders’ subconsciously rigged standards, to one in which they’re not even interested in trying. And if you know where to look, you can find traces of those terrifying, antisocial beatniks here and there throughout the media of the 1950’s. Indeed, there are even a handful of overt Beatnik Movies from that era, prefiguring the hippie and biker films of the late 60’s and early 70’s— but in their attitudes toward the restive youngsters they depict, the 50’s-vintage beatniks flicks perhaps have even more in common with the almost uniformly negative punksploitation pictures of the 80’s. The Bloody Brood is an especially intriguing example, because more than just a beatnik movie, it’s a Canadian beatnik movie, demonstrating that the beat scene in its totality (as opposed to just the art originating within it) had international reach.

We begin with a pack of beatniks hanging out in a bar. Among them, only Dave (A Cool Sound from Hell’s Ron Taylor) has gone all in on the expected look— turtleneck, bad hair and worse glasses, everything but the beret— and the de facto leader of the group is the completely normal-looking Nico (Peter Falk, of all people!). We’ll later learn that Nico’s position is due at least partly to his central role in supplying the scene with marijuana and heroin, but it’s clear right now that it’s also partly because Nico really is as intelligent and as radically individualistic as the other beatniks just think they are. An elderly newspaper vendor walks in, and after teasing him for a bit in terms too abstruse for him to follow, Nico buys a paper and tips well enough for the old man to get good and loaded on the spot. The hawker never gets to drink that whiskey, though. No sooner does he place his order than he keels over with a massive heart attack. Nico is fascinated. He’s never seen a life end up close and personal like that, and it dawns on him as he watches the old man’s final moments that here, at last, is something with meaning. His closest friend among the other beatniks, an ulcerous and perpetually dissatisfied director of television commercials named Francis (Ron Hartmann, from Virus and The Reincarnate), doesn’t understand what Nico is driving at with all this sudden talk of the Ultimate Kick, but he’ll catch on more than he’d ideally like to a few nights later.

One of Nico’s regular customers, a man by the name of Arnold Curtis, is out of town at the moment, and he’s favored the pusher with the keys to his apartment. What better place to throw a party than the home of somebody who isn’t around to complain about wrecked furniture, stolen valuables, or pissed-off neighbors, right? It happens, though, that somebody has sent Curtis a telegram this night. Delivery guy Roy Bowman (William R. Kowalchuk) arrives when Nico’s shindig is in full swing. A stranger to everyone there, Roy is barely even noticed by most of the guests, but the host unfortunately marks him very well indeed. Ever since he saw that old newsie die, Nico’s been craving an encore performance, but that isn’t the sort of thing one lucks into twice. And although Nico is plainly depraved enough to kill somebody, he’s also sharp enough to appreciate the risks inherent in doing so. A delivery boy, though— and an officially unoccupied apartment to which the dope-dealer has no formal ties whatsoever… Quickly enlisting Francis as an accomplice, Nico invites Roy inside, cannily offering the cash-strapped young man something to eat. The hamburger which Nico then instructs Francis to cook for him is liberally seasoned with ground glass, and after Roy finishes it and goes on his way, the conspirators follow him surreptitiously so as to be there to witness the results when the booby-trapped burger takes effect. Francis is horrified when it happens, but he has to admit that Nico was right about one thing. Murder is indeed one hell of a kick!

Responsibility for investigating Bowman’s death falls to a police detective called McLeod (Robert Christie, of Hyper Sapien: People from Another Star), whose first instincts lead in two contrary directions. On the one hand, this could be a negligent homicide case. Maybe some greasy spoon has a rat problem, and the sabotaged bait meat meant for the rodents found its way into Roy’s dinner by mistake. But if it was murder, then the closest thing to a suspect that McLeod can see is the dead man’s older brother, Cliff (Jack Betts). Both Bowman lads had recently taken out life insurance policies, naming each other as their beneficiaries, and that could conceivably be spun as a motive if you squinted hard and looked at it from a very cynical point of view. Even McLeod doesn’t find that interpretation terribly convincing, however, and it no longer sounds convincing at all once the detective gets a chance to speak to Cliff at length. The surviving brother’s anger is too hot and too close to the surface to be put on, nor does Cliff’s open scorn for the police strike McLeod as an affectation likely to be adopted by a guilty man trying to deflect suspicion. That leaves McLeod more or less nowhere, and he knows it. Indeed, the detective takes such a dim view of his own prospects that he’s prepared to cooperate (in an unofficial, plausibly deniable capacity, of course) with Cliff’s stated plans to pursue his own vigilante investigation of Roy’s death. After all, maybe someone who saw or heard something would talk to the victim’s brother when he wouldn’t talk to a cop. McLeod hands over the one solid clue he has, Roy’s checklist of his delivery roster for the night he died.

Incredibly, Cliff gets lucky on his very first attempt. The sullen young bitch who lives across the landing from Curtis’s apartment gripes to Bowman about all the noise coming from the supposedly empty unit on the night in question, and while Cliff sits outside the door pondering that, Dave the beatnik just happens to swing by hoping to catch Nico at “home.” Cliff extemporizes a cock-and-bull story about being a friend of Arnold Curtis, and asks Dave if Nico would know where to find the absent man. The next thing he knows, Dave is leading him to the Digs, the nightclub that serves as the nexus of Toronto’s beat scene. That in turn puts Cliff into contact with Ellie (Barbara Lord), just about the only person at the fateful party apart from Nico and Francis who remembers seeing Roy come to the door. Unfortunately, it also brings Cliff to the attention of Nico himself, rather earlier than Bowman was prepared to confront his brother’s killer. Nico sees right through Cliff’s cover story when they meet face to face a few nights later, and although he satisfies himself that the interloper doesn’t know anything as yet, it’s plain enough to Nico that Bowman spells trouble for him and Francis. Obviously something will have to be done about that.

Nico has trouble on a second front, too. Although he sells a fair amount of his dope personally, he also employs a pair of subcontractors known as Studs (The Mask’s W.B. Brydon) and Weasel (Michael Zenon, of Rituals). They serve him both as pushers and as hired muscle, which should tell you that Cliff will be dealing with them, too, at some point. It’s convenient for Nico that Studs and Weasel are good at their jobs, but rather less convenient that they themselves realize that. Studs thinks they should be getting a bigger cut, and he knows too much about Nico’s business for the boss to afford not to keep him happy. Furthermore, Nico has, if not exactly a boss of his own, then at least the next most annoying thing, in the form of a German gangster called Stefanic (Lloyd Jones, maybe? His name is in about the right spot in the credits, anyway) who supplies him with his illicit wares. This fellow has been concerned about Nico ever since he fell in with the beat scene. On the one hand, that bunch buys a whole lot of drugs, so Nico’s association with them is one of the best illegal business opportunities in town. But on the other, it hasn’t escaped Stefanic that Nico has been internalizing more and more of the beatniks’ philosophy. The drug trade may be a criminal enterprise, but it’s still commerce, and the German knows as well as Nico does what the crowd at the Digs think of commerce. Stefanic just wants to make sure that Nico continues to remember what’s really important in life, you know? So imagine how he’d take it if he ever found out that Nico had killed a man just for the chance to watch him die— let alone if he found out that the victim’s brother was not just snooping around after clues to the perpetrator’s identity, but getting closer to the truth than the cops would ever have managed on their own!

On May 21st, 1924, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb teamed up to abduct and murder Bobby Franks, Loeb’s cousin, who lived across the street from him in the Kentwood neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side. Media and public alike were mesmerized by the crime, for several reasons. First, there was the sheer ghastliness of the murder. Leopold and Loeb had lured Franks into a car which they had rented for the purpose under assumed names, jammed an icepick through his skull while simultaneously strangling him, and then dumped the body over the state line in Indiana after stripping and disfiguring it with hydrochloric acid in the hope of rendering Franks unidentifiable. The shockingly young ages of victim and perpetrators alike were a factor as well; Franks was just fourteen years old, while Leopold and Loeb were eighteen and nineteen respectively. Then, of course, there was the identity of the defendants’ lawyer, the famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) Clarence Darrow. But the most attention-getting aspect of the case was the motive behind the killing— there wasn’t one, at least in any ordinary sense of the term. Leopold and Loeb didn’t rob Franks, nor did the boy’s death bring them any other form of material gain, like, say, an inheritance or a mob bounty. Even the ransom notes that the killers sent to Franks’s parents were designed more to throw the authorities off the scent than to line Leopold and Loeb’s pockets. And in any case, both lads were the sons of millionaires, so it wasn’t as though they needed the $10,000 they demanded from Jacob Franks, ostensibly to buy the already dead kid’s safe return. They harbored no grudge against their victim, had no rivalries with him, whether social, familial, or romantic, had no cause to resent or to envy him in any way. The murder of Bobby Franks wasn’t even a sex crime, for although Leopold and Loeb did pour acid on the corpse’s genitals, their object in doing so was to obscure the fact that Franks had been circumcised, thereby depriving the authorities of one more clue to his identity. Indeed, Leopold and Loeb planned out their crime with no specific victim in mind whatsoever. Franks was merely the most convenient target when the time came to carry it out.

So why did they do it? Clarence Darrow assembled a small army of psychiatrists to explain to the court the abnormal development of the defendants’ personalities, but from the killers’ own perspective, they killed Bobby Franks to prove a point. Leopold was infatuated with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly with the concept of the Übermensch, the innately superior human to whom conventional morality supposedly does not apply. He believed that he and Loeb— but Loeb especially— were just such people, and almost from the beginning of their relationship, he made a hobby of inciting Loeb to ever greater lawlessness (with himself acting as loyal accomplice) in order to demonstrate their emancipation from the social and moral constraints that bound the rest of humanity. Killing Franks was to be their ultimate experiment in living beyond good and evil, a perfect, insoluble transgression that would establish once and for all their status as Supermen. Nothing similar had come to light before in all the annals of American crime, so it’s only to be expected that the case would rivet popular attention.

Naturally, no story so compellingly weird could long remain unexploited by writers of fiction, and thinly veiled versions of Leopold and Loeb would recur in virtually all media for decades thereafter. The most famous example, of course, is Rope, the 1929 stage play by Patrick Hamilton, which Alfred Hitchcock would adapt for the screen in 1948. There have been plenty of others, though: the novels Little Brother Fate, Nothing but the Night, and Compulsion (the latter of which also became a movie in 1959); another play, called Never the Sinner; Tom Kalin’s film, Swoon; and even an off-Broadway musical entitled Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story. And more to our present point, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to discern Leopold and Loeb hiding behind Nico and Francis in The Bloody Brood.

Obviously there were no beatniks yet in 1924, but the facts of the Leopold and Loeb case just as obviously lend themselves to being reimagined through a beat lens, at least so long as it’s the fearsome early beatniks we’re talking about. Young guys holding to a philosophy radically at odds with consensus values, murdering in cold blood to set themselves yet further apart from the masses— what better basis for an alarmist thriller about These Kids Today in 1959? What’s most remarkable about The Bloody Brood, though, is how willing it is to give its beatniks a fair hearing. Nico, significantly, was originally an outsider to the scene, for all his current dominance over it. Most of his associates, customers, followers, and hangers-on are portrayed more as puzzling eccentrics or freewheeling hedonists than as genuinely dangerous mind-terrorists. And when the screenwriters (four of them!) let the other beatniks speak for themselves, at least a few of them— Ellie especially— are permitted to seem reasonable underneath the opaque slang, even if the filmmakers show little sign of understanding the causes of their cynicism toward mainstream values. Furthermore, although I doubt there was any deliberate intent behind this detail, it’s noteworthy that the one character who ever musters an actual argument against the beatniks’ point of view is Stefanic, the crime boss. In context, that in itself looks almost like an argument in their favor.

Returning now to Nico specifically, The Bloody Brood will come as a revelation to anyone who knows Peter Falk only, or even primarily, as Columbo. The only thing about Nico that could fairly be described as unassuming is his taste in suits. He commands attention whenever he opens his mouth, spinning skeins of seductive wickedness with an air of absolute authority. It’s clear, too, that when Nico talks of “kicks,” he has a considerably more expansive meaning in mind than most of his associates. He’s no mere amoral thrill-seeker, nor even an ordinary nihilist. Rather, he’s a man at war against the emptiness he now perceives in everything he was ever taught to value, and whose escalating transgressions are driven by a misaimed hunger for substance and authenticity. When he and Francis murder Roy Bowman, it’s an attempt to assert their personal significance in the cosmos by controlling somebody else’s destiny for a change. And refreshingly, looking back from this era in which everything must have a meticulously defined origin story, we never do learn just what went missing from Nico’s life, or how it happened; he remains a deadly enigma to the very end. Falk’s performance in the part is genuinely chilling, leveraging the discordance between his smallish stature and unimpressive physique on the one hand, and the cheetah-like intensity which he affects for the role on the other. He’s especially good when he gets to play opposite Ron Hartmann, enacting the positive feedback loop of violence between charismatic monster and angry, easily-led weakling that has become so horribly familiar in the decades since the massacre at Columbine High School. It’s perhaps the ultimate testament to Falk’s effectiveness as a villain that not once was I tempted to mumble a confused-sounding, “Oh— there’s just one other thing…” on his behalf despite several moments when the circumstances of the scene might be read to invite that particular bit of snark.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact