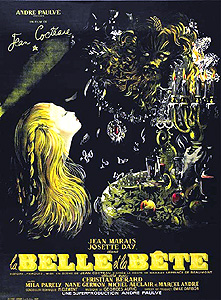

Beauty and the Beast/La Belle et la Bête (1946) ***½

Beauty and the Beast/La Belle et la Bête (1946) ***½

One disadvantage of being born as late in the 20th Century as I was is that by the time I’d arrived on the scene, Walt Disney had already come through and fucked up most of the A-list fairy tales. Like most children, I was a sucker for stories about magical worlds full of strange creatures and supernatural forces, but by the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, it was something of a challenge to find anything in the children’s section of the typical public library save the Disneyfied version of any fairy tale for which a Disneyfied version existed. Now many little kids adore Disney, but so far as I can remember, I’ve never been one of them. I couldn’t really have explained why at the time, but in retrospect, I believe it was because the Disney universe (and this applies about equally whether we’re talking about Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs or a ten-minute Mickey Mouse cartoon) is ultimately safe and orderly and ever so goddamned cheerful, while from a very early age, I liked my fantasy worlds to be violent, threatening places. Other children might have focused on the handsome prince awakening his beloved with a kiss, but what I cared about was the wicked witch turning herself into a fire-breathing dragon. It is probably to be expected, then, that I had a special fondness for the story of Beauty and the Beast. (Although it was by no means my favorite fairy tale— that was “The Three Billygoats Gruff.”) For one thing, Walt Disney didn’t get his grubby, cryogenically preserved mitts on it until after my childhood was safely over. But more importantly, it is among the darkest and most subversive of Western fairy stories, for in it, the handsome prince is the menacing monster. Post-kiss transformations aside, how often does the monster get to kiss the girl and live happily ever after?

Celebrated French filmmaker Jean Cocteau obviously got that point, too. His interpretation of Beauty and the Beast is explicitly about a girl who voluntarily enters a realm of what most people would consider nightmares, and falls in love with the nobility she unexpectedly finds there. Of course, since it’s a French movie from the postwar era, it naturally also juxtaposes that world of dreadful wonders against a fairy-tale rendering of middle-class banality, but that’s a sideline we can safely leave to the dissections of the film-studies bores. Cocteau’s Beauty (Josette Day) is the youngest daughter of a prosperous merchant (Marcel André) who has just fallen on hard times. Three shiploads of imported goods have apparently been lost at sea, and the sudden downturn in the family’s fortunes is playing havoc with the social lives of Beauty’s sisters, Félicie (Mila Parély) and Adélaide (Nane Germon). Their no-good brother, Ludovic (Michel Auclair), meanwhile, is facing default on a monster gambling debt, and the moneylender (Raoul Marco) to whom he turns to bail him out forces him to sign a contract putting up his father’s furniture as collateral. Life is rough, in other words, and the exploitation-based relationships Beauty has with every member of her family except for her dad aren’t helping the situation any. Even Beauty’s sort-of boyfriend, Avenant (Jean Marais, from the 1964 version of Fantomas and its sequels), is more a part of the problem than he is of the solution. Avenant pressures Beauty to leave her family (which would entail abandoning her father to deal with his useless older offspring unaided), and he’s much more insistently randy than Beauty is willing to countenance.

Then, at last, some good news arrives. A rumor reaches Beauty’s father from the docks to the effect that one of his ships has survived after all. Dad sets off for town to see what’s really going on and, if possible, to get some of his creditors off his back by selling whatever the surviving ship was carrying. Ludovic breathes a sigh of relief at the thought that he’ll be able to pay off his debts with something other than the household furnishings. Félicie and Adélaide make extravagant demands for presents from town. But all Beauty wants is for her father to bring her back a nice rose. As it happens, only Beauty will be getting her wish. There’s some kind of problem at the docks (exactly what isn’t clear), Dad’s creditors pounce on him the moment he shows his face in their offices, and it looks like the family is pretty well screwed after all. And as the final kick in the ass, Beauty’s father gets lost in the woods while attempting to ride home during a foggy night.

That’s when things take a turn for the weird. Dad’s wandering and circling through the forest eventually leads him to a castle the existence of which he had never suspected. It appears at first glance that the place is deserted, but it quickly becomes evident that something dwells within its walls— just nothing human or natural. The doors to the stable open by themselves when Beauty’s father leads his horse to them, then slam shut behind the animal, leaving its master outside. The castle’s main gate is similarly self-actuating, and the arm-shaped candelabras lining the entry hall walls are not only self-lighting but obviously alive. In a chamber at the end of the entry hall, the lost wayfarer finds a table laden with rich food and fine wine, set for a single guest. Not knowing what else to do, Beauty’s father eats, drinks, and falls into a troubled sleep under the gaze of the animate carvings that adorn the nearby fireplace. No harm has come to him by the time he awakens, however, and so he prepares to resume the journey home. But on his way through the garden toward the stable, he spies a vibrant rose, and remembering Beauty’s request, he plucks it from its trellis. Suddenly, a rasping, inhuman voice commands him to stop where he is, and a splendidly attired man with the head of a lion (also Jean Marais) strides out from amid the foliage. The Beast informs Beauty’s father that he has taken the one thing in all the castle and its grounds which is off-limits to visitors, and that he will pay with his life for the transgression. The only way the man can save himself is if one of his daughters will agree to deliver herself to the Beast in his place. The Beast lends his condemned guest an enchanted horse, and swears him to return the next day in the event that none of his daughters will agree to the trade. Beauty, arguing plausibly that the whole mess would never have happened if she hadn’t asked her father to bring back a rose, makes the journey to the Beast’s castle, where she gets a rather different reception than she had anticipated.

By far the greatest strength of Beauty and the Beast is its unsettling visual strangeness. Magic in fairy-tale movies is typically portrayed either in matter-of-fact terms or in a spirit of joyous wonder, but Cocteau battens unshakably upon an important point that those conventional portrayals miss— that the instinctive first response of practically anybody witnessing an apparent abrogation of natural law is likely to be skin-crawling dread if not outright terror. The Beast’s castle is a domain of total irrationality, and even its benevolent magic seems threatening initially. When Beauty tells her sisters late in the film that at the Beast’s castle, “invisible hands dress me,” she’s describing a phenomenon that would take a hell of a lot of getting used to, and Cocteau never loses sight of that. When Beauty’s blankets writhe down toward the foot of the bed to accommodate her as she prepares for a night’s rest, Cocteau rigs it so that you wonder how she manages not to run screaming from the room instead. In terms of ambient eeriness, Beauty and the Beast is in the same league as Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr.

Unfortunately, the one gaping hole in that ambient eeriness is the Beast himself. Cocteau tries, and Jean Marais tries even harder, but the Beast never projects the sort of presence that he should. Part of the problem is Marais’s voice, which simply does not have the requisite power— despite all the snarling, it’s the voice of an ocelot or a civet cat rather than a lion. But I think the stricter limitation on the Beast’s effectiveness is, paradoxically, a makeup design that is too faithful for its own good to his traditional folkloric appearance. Simply put, dress a man up like a lion with the technology of 1946, and you don’t get a lion-man— you get Sweetums from “The Muppet Show.” In order to achieve the necessary effect, Cocteau ought to have re-conceptualized the Beast, basing the design for the character upon an animal that is in no way cute or cuddly. Picture the impression it would have made during the initial reveal if instead of an adorable, fluffy lion, the Beast had been a hyena or a mandrill or a Komodo dragon. The excessive cuteness of the Beast is actually a complaint I’ve had with every adaptation of the story I’ve seen, so it can hardly be said that Cocteau was behind the curve. Nevertheless, I still think that Beauty’s transition from fearing the Beast to loving him would have a great deal more meaning with a character design that didn’t immediately cry out for hugs and noogies.

But caveats about the Beast aside, and despite an ending that makes very little sense, either by real-world logic or by fairy-tale logic, Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast remains the yardstick by which any serious cinematic fairy tale must be judged. It is a beautiful, haunting film that gets tremendous mileage out of the simplest visual tricks, and it follows the story very closely, without apologizing for any of its medieval irrationality. Although he can be a flashy director, Cocteau mostly has the good sense to use his more obtrusive directorial flourishes in the service of the story, as opposed to merely showing off. (The one serious exception is his avowed policy of using music that is tonally out of synch with the action onscreen. It’s distracting at best, and downright ridiculous at worst.) All of the performances are good within the limits of the material, and each of the women approaches actual greatness in at least a couple of scenes. There’s even a bit of successful humor. All around, Beauty and the Beast is one of the best fantasy films of its era.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact