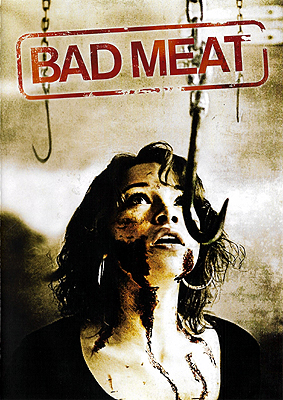

Bad Meat (2011/2013) **

Bad Meat (2011/2013) **

It can be surprisingly difficult sometimes to tell whether a not-very-good movie got that way because its creators were trying way too hard, or not quite hard enough. In the case of Bad Meat, I think it might actually be both at once. This loose-jointed merger of the Captivity & Torment and “zombies, but not, you know, zombies” subgenres lays it on awfully thick, but never really goes anywhere or does anything with all its edgy excess. And although it is in many respects a more professional undertaking than I’m used to seeing from direct-to-DVD horror movies released through independent video labels, I’m not entirely convinced that Bad Meat should even be considered a finished film.

Camp Hardway is one of those “tough love” places where conservative middle-class parents send their delinquent teenaged offspring to be set on the straight and narrow by sadists, perverts, and psychopaths. As camp director Thomas Kendrew (Mark Pellegrino, from Prayer of the Rollerboys and The Number 23) puts it to his latest crop of inmates with more honesty than his paying customers might appreciate:

Your parents want kids who will respect them for the sacrifices they’ve made. Kids who will take responsibility for their actions. Kids who will follow the rules. In short, your parents don’t want you, so they gave you to me. |

Due to the unusual number of castmembers with real acting careers, who expect to be paid in money rather than beer, weed, and unspecified favors to be negotiated at some future date, said crop of inmates consists of but three boys and three girls. Their transgressions cover a disproportionately broad range of severity, however. At the high end are Estelle the thief (Jessica Parker Kennedy, of Behemoth and Cam) and Rose the budding arsonist (Elizabeth Harnois, from Solstice and The Osiris Chronicles). At the other extreme, Kelly (The Editor’s Samantha Hill) did no more than to mistake her pastor for someone who could be trusted with the information that she found herself uncomfortably attracted to one of the female counselors at camp last summer. The boys all fall somewhere in the middle zone. Tyler (James Franco’s less famous brother, Dave, who was also in The Shortcut and the Fright Night remake) led a disruptive— and perhaps more damningly, successful— animal rights protest to abolish the dissection lab unit in his high school biology class. Billy (Joe Dinicol, from Diary of the Dead and The Marsh), in an ironic inversion of Tyler’s background, got sent to Camp Hardway for cutting up a dead cat; Mom and Dad misinterpreted his scientific curiosity about a carcass he found in the woods as a sign that they had the next Eric Harris on their hands. And as for Mark (Tahj Mowry), his story never really comes out. From what we see of him, it could equally well be a matter of recreational drug use or just his affluent, social-climbing parents becoming acutely embarrassed of his ghetto affectations. But whatever brought the kids of Camp Hardway into Kendrew’s custody, he and his staff— Skullet (Aaron Berg), Wolfe (Brian Nugent), and Peters (Monique Ganderton, who played miniscule roles in 30 Days of Night: Dark Days and The Wicker Man)— can be counted on to make sure they all enjoy eight solid weeks of character-building misery!

There’s a factor that nobody has figured on, however, and that’s Manuel (Omar Alex Khan, of Pay the Ghost and Mother’s Day), the Camp Hardway cook. Kendrew and his minions aren’t much less extravagantly nasty to him than they are to the kids, and this session, Manuel has finally had enough of their shit. Because he routinely prepares separate menus for staff and inmates— proper and reasonably appetizing meals for the former, deliberately repellant subsistence fare for the latter— the cook has no trouble targeting his revenge solely at those who actually deserve it. And what a revenge it is! Not long after Tyler, Rose, and the rest begin their stay, Manuel whips up a stew sabotaged with tainted meat, the efficacy of which he first tests on the camp’s two guard dogs. All four screws begin feeling the effects late that night, after they’ve each retired to their quarters to unwind after another hard day of abusing minors. Skullet feels his first symptoms while perving on the girls’ barracks, Wolfe and Peters in the midst of some comically kinky sex, and Kendrew himself while reading in bed about his hero, Adolf Hitler. Manuel waits until he’s sure the lot of them are puking up and shitting out their guts before finalizing his revolt by driving off in the Jeep Wagoneer that serves as Camp Hardway’s only link to the outside world.

At first, the kids are bewildered when no one comes to wake them at the crack of dawn to begin the new day’s torments. Then they start to worry that their jailers’ apparent absence is the setup for some sort of trap. Finally, they become elated when they discover that Kendrew and the others aren’t missing, but are rather laid up with some illness every bit as disgusting as themselves. Manuel’s theft of the Jeep limits the inmates’ prospects for escape, however, and in any event, Rose refuses to leave until they’ve sprung Tyler from the semi-subterranean solitary confinement cell where he spent the night before. The trouble there is that Estelle’s lock-picking skills don’t extend to padlocks. Rescuing Tyler will require finding and securing Kendrew’s own keys. And the trouble with that is that the germs running amok in the camp administrators’ guts are also doing a number on their brains. Eventually, the damage to the latter will outpace the damage to the former, and then the staff of Camp Hardway will rise from their befouled beds to go fully 28 Days Later… on the teens in their charge.

I’m neither kidding nor exaggerating for effect when I say I’m not convinced that Bad Meat was ever truly finished. I first suspected that something was up when I saw all the girls of Camp Hardway sporting those low-rise jeans. Although I guess it’s plausible for Winnipeg (where Bad Meat was shot) to be a few years behind the curve of women’s fashion, that look was decidedly on the way out by 2011, giving this movie almost a period quality that would have made little sense for its creators to pursue as a conscious choice. And in fact it turns out that the bulk of the film was shot between late 2007 and early 2008 by Rob Schmidt, a director whom my readers are most likely to know for his 2003 backwoods horror flick, Wrong Turn. The company backing Bad Meat went out of business, though, something like two-thirds to three-quarters of the way through the principal shooting schedule. Production shut down, Schmidt moved on to other projects, and Bad Meat disappeared from sight for more than four years. Then, late in 2012, it unexpectedly surfaced on the distributors’ pickup market, having supposedly been completed the year before by a director named Lulu Jarmen— of whom no one had ever heard before, nor ever has heard again. The consensus of speculation has it that Jarmen is really Schmidt himself, working under a pseudonym to shield his good name from this movie’s radioactivity. I don’t feel qualified to have an opinion on that. My speculation, rather, concerns what specifically Jarmen (whoever that may be) added, and how that new footage relates to what Schmidt shot in 2007-2008.

What I didn’t mention before about Bad Meat’s story is that it has a frame, in which a young person of indeterminate sex, swathed head to toe in bloodstained bandages, lies silent in a private room in some hospital’s intensive care unit, laboriously typing out a statement for the authorities on a computer beside his or her gurney. Obviously this is supposed to be the lone survivor of the events at Camp Hardway, but we’re just as obviously meant to take it as a major mystery which kid made it out in the end. Then it’s supposed to be a SHOCKING TWIST! when Mystery Teen cuts off their own facial bandages to get a look at themselves in a mirror, only to discover that they no longer have anything much resembling a face. DUN-DUN-DAAAAAAHHH!!!! Now we’ll never know the survivor’s true identity! The whole thing is nonsense, of course. First of all, any fool can tell from jump that Mystery Teen wouldn’t be wrapped up like King Tutankhamen dipped in raspberry preserves if there were a square inch of intact skin left anywhere on his or her body, so that ending isn’t telling us a thing we didn’t already know. And secondly, there’s no indication that Mystery Teen is suffering from amnesia, so all it would take to establish their identity definitively is to read their fucking statement. It’s my belief that these framing sequences are Lulu Jarmen’s work, added in the hope of making up for an altogether different ending that was never shot at all. My evidence for this is as follows:

1. The main plot doesn’t come to anything like a proper conclusion even now. The action simply fades out just as what ought to have been the climax is getting started, returning us for good and all to Mystery Teen’s bedside in the ICU. Furthermore, the bullshit enigma of Mystery Teen’s identity is exactly the kind of desperation measure that someone might try in the unenviable position of having to whip into releasable shape a movie without an ending, under circumstances that ruled out reassembling the cast to film what had originally been written. 2. Although the actor playing Mystery Teen is never revealed, they’re unmistakably not any of the kids from the Camp Hardway scenes. No one in the core cast has Mystery Teen’s sexually ambiguous build (there’s genuinely no telling whether we’re looking at an unusually flat-chested girl or an unusually round-hipped boy), and the one feature of theirs that we are shown— their eyes— doesn’t match those of anybody we see at the camp, either. (Amusingly, Mystery Teen’s eyes also don’t match the ones on the no-face mask in the final scene.) 3. In ways that are difficult to pinpoint, the quality of the cinematography varies drastically between the framing sequences and the main body of the film. Whatever else we might say about them, the bits set at Camp Hardway invariably look like they were shot for a real movie. The bits in the ICU all look like they were always destined for the kind of dreck that usually sneaks out unheralded onto DVD, as Bad Meat ultimately did. |

Regardless, it’s a bit of a shame that we’ll never see the Bad Meat Rob Schmidt set out to make, because it was shaping up to be at least a little better than what we actually got. I realize I’m grading on a ridiculously forgiving curve here, but the mere fact that most of this movie was plainly made by people who do this stuff for a living, and have trained accordingly, gives Bad Meat a noticeable edge over many, and perhaps most, other films in its market segment. None of the actors seem to fear the camera, nor do any of them fixate on it like a potential mate they’re trying to impress. There’s a decent amount of variation in how the shots are composed, and everything is lit like someone gave at least a few minutes’ thought to how the finished product should look. The gore effects in the Camp Hardway section are quite good, in stark contrast to Mystery Teen’s sorry hamburger head. There are even a few scenes that might be effective if you saw them in isolation, or if the movie surrounding them were more consistent. For instance, Kendrew’s psychological evaluation interview with Rose is fairly astute regarding both the mentality of the troubled adolescent and the vulnerabilities that it creates for authoritarian bullies to exploit. And on a cruder level, our last look at Tyler, still trapped in solitary as the disease-maddened administrators attempt to muster up enough problem-solving intelligence between them to cope with a locked door, is a memorably horrific image.

Alas, none of the items in Bad Meat’s credit column have the impact they ought to, because the movie as a whole is tonally all over the map, in ways that strongly suggest the filmmakers have lost theirs. Some elements, like Kendrew’s choice of relaxing bedtime reading, or the black-leather S&M devil-girl outfit that Peters wears for most of the picture, would be most at home in a Troma-style splatstick farce, but Schmidt’s direction is too sober for the movie to succeed as one of those. Manuel’s preparation of the plague-bearing stew and subsequent “resignation” have the detached, jet-black absurdity of an early Paul Bartel project, but literally nothing else in Bad Meat does. The course of the administrators’ illness begins at the most bathetic extreme of gross-out comedy, then passes through harrowingly believable medical horror (especially when seen through post-COVID eyes), only to settle in “Resident Evil on five dollars a day” territory. And although Schmidt seems constantly to be flirting with some manner of satire, he never quite makes up his mind what specifically he might want to satirize. Like, it feels as though Rose’s vegetarianism, Tyler’s animal-rights activism, Billy’s facility with a dissecting kit, and the camp staff’s habit of mistreating the guard dogs are collectively supposed to mean something in a movie where people who eat contaminated meat turn into cannibalistic monsters— but they just don’t, so far as I can tell. Similarly, we might try to extract some kind of message about the vile breed of real-world juvenile penal institution on which Camp Hardway is modeled, but none ever comes into focus beyond the self-evident “they’re bad, m’kay?” The biggest problem there is that Kendrew and company are so cartoonishly odious to begin with that becoming mindless rage-zombies noticeably improves their dispositions! I suppose that too might have been made to mean something, but Bad Meat never does the required work on that front, either.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact