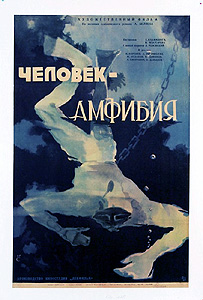

Amphibian Man/Chelovek Amfibiya (1961) ***

Amphibian Man/Chelovek Amfibiya (1961) ***

This little tour of Soviet genre cinema I’ve been taking courtesy of Baltimore’s Charles Theater has yielded one unexpected treat after another. Russian movies from the Communist era have a reputation for being either artlessly propagandistic or unstintingly glum and mopey, and lord knows I’ve seen a few that fall into both of those categories (and occasionally into both of them at once). But as I’m seeing to my ever-increasing delight, there was some weird, weird shit going on behind the Iron Curtain, and it’s really a shame that we on the other side got to see so little of it. What’s more, the variety of that strangeness exceeds anything I might have guessed at on my own. Amphibian Man may be the prize-winner, though. My limited prior exposure to Russian sci-fi and fantasy had prepared me for smugly triumphal space operas; it had prepared me for unabashedly goofball stories of myth and magic with a juvenile bent; I even knew that if one looked hard enough, there were a couple of honest-to-Marx horror movies to be had. But a sci-fi fairy-tale romance about a Cuban gill-boy and his impossible love for the fiancee of the local Capitalist Pig? No. That I was not prepared for.

To be honest, I’m just kind of assuming that Amphibian Man is set in Cuba (pre-revolution Cuba, obviously), on the grounds that it was actually shot there. What we really get is sort of a mish-mash of cultural tics from all over the Spanish-speaking Americas, as enacted by a gaggle of Slavs (plus the occasional Tatar!) in brownface— if this movie teaches us anything about the character of the Russian people, it’s that the average Ruskie in the early 60’s was apparently no better at distinguishing between the various nations of Latin America than the average Yank. Whichever country it’s supposed to be, the specific setting is a seaside city where one of the major industries is pearl harvesting, and it is in said industry that that Capitalist Pig I mentioned currently makes his living. The man’s name is Don Pedro Zurita (Mikhail Kozakov), and he naturally does none of the actual diving himself, but rather stays on the deck of his ship, the Medusa, grumbling about what a bunch of lazy bums his employees are. Zurita is finding them especially irksome at the moment, because all of the neighborhood proles have their Speedos in a bunch over the Sea Devil, a gill-man sort of beastie that is reputed to do things like sink small boats and abduct nuns from ashore. Zurita doesn’t believe in the Sea Devil, of course, but we know he’s real, because we see him ourselves just minutes after the opening credits— and oh, man… if you thought the monster suits in War-Gods of the Deep were weak… I’ll give the design for the Sea Devil this much credit: with its silver coloration, uniform covering of semicircular scales, and low-slung dorsal fin, it is much more honestly fish-like than any of its competitors, save perhaps the one in Destination Inner Space. It’s just that it looks a hundred times more like a man in a suit than any but the very worst of them.

Zurita is about to become a believer, however. With him aboard the Medusa this morning are a broken-down old drunk named Baltazar (Anatoly Smiranin) and the latter man’s teenaged daughter, Gutiere (Anastasiya Vertinskaya). Baltazar had been a subordinate partner in many of the schemes that made Zurita the rich man he is today, but the terms of those partnerships were always such that the old man somehow ended up owing Don Pedro a shitload of money, even as Zurita himself reaped enormous profits. By now Baltazar is in hock up to his eyeballs, a state of affairs which bears directly upon Pedro’s relationship with Gutiere. Zurita, you see, is in love with Baltazar’s daughter— who, for her part, finds Pedro rather repellant— and he hopes to use that mountain of debt as a means of forcing Baltazar to arrange their marriage. Baltazar is reluctant to lean too heavily on Gutiere, but he also knows perfectly well that Zurita has him by the balls. Anyway, when the subject of possible nuptials between Pedro and Gutiere comes up in conversation, and Zurita makes to seize a kiss from the girl, Gutiere becomes so incensed that she actually leaves the ship and goes swimming off at top speed toward the open ocean. That’s alarming enough, but then one of Zurita’s men sights a shark’s dorsal fin on what looks like an intercept course. The Sea Devil stories have all the divers too spooked to go to Gutiere’s rescue, so Pedro takes off after her in a rowboat, hoping to reach her before the shark. Zurita doesn’t get there in time, but the Sea Devil does. The gill-man makes short work of the shark (well, it’s better than the fish-fight in Devil Monster, anyway…), then dives to the sea floor to lift the now-unconscious Gutiere to safety and deposit her in Pedro’s skiff. Zurita takes full credit for the rescue after he gets the girl back aboard the Medusa, saying nothing about his strange encounter to anyone. But he knows perfectly well what he saw, and he’s shrewd enough to spend the next several days pondering whether there might be some way to turn that knowledge to his advantage.

Meanwhile, a reporter named Olsen (Vladen Davydov) pays a visit to an old friend of his, the renowned medical researcher Dr. Salvator (Nikolai Simonov). Salvator is much respected around these parts for his extraordinary diagnostic and surgical skills— later on, Baltazar will matter-of-factly refer to him as “God.” (Deifying a man called “Salvator?” No, that’s not heavy-handed at all…) He’s also a marine biologist, though, and it is in the latter capacity that Olsen has come to see him. Olsen wants to know what Salvator thinks about all this Sea Devil business; the scientist’s answer is, shall we say, equivocal. Yes, he swiftly denies the existence of devils, either marine or terrestrial. However, he also launches off into a rather odd speech outlining a utopian vision of all the world’s downtrodden making a new life for themselves on the bottom of the sea, and then presents Olsen with proof that there is at least one tiny respect in which his eccentric vision of Earthly paradise is not utterly ridiculous. That gill-man all the natives are so afraid of? He’s Salvator’s son. And as we are about to learn, he isn’t really a gill-man at all, or at least not in the conventional sense. The scaly skin and the finny feet and the weird, pointy face are merely a costume he wears when he’s out in the water— which suddenly and most unexpectedly puts the monster suit in a new and altogether more forgiving light. Underneath it, Ikhtyandr (Vladimir Korenev) is a quite handsome (if also somewhat effeminate) lad. Nevertheless, he does indeed have a set of gills, taken originally from a shark of some moderately large species. Salvator installed the gills many years ago, when Ikhtyandr contracted a deadly lung infection; shifting the boy to water-breathing bought Salvator the time he needed to overmaster his son’s disease and save his life. The kid’s been equally at home on land and underwater ever since, and it was the success of Ikhtyandr’s gill-graft that inspired Salvator to conceive his loony scheme for the People’s Republic of Atlantis. It’s all a big secret, of course, but since Olsen’s newspaper is an implacable foe of political corruption, constantly under threat of being shut down by the authorities, Salvator figures the journalist can be trusted to keep his mouth shut. He’s got secrets of his own, after all.

As it happens, Olsen’s trustworthiness really isn’t the issue. First off, Zurita has a brainstorm, and hatches a plan to catch the Sea Devil and press him into service as the ultimate pearl diver. To that end, he and Baltazar begin closely examining the seafloor in those areas where the creature has most often been seen, and Baltazar eventually discovers the grated-off cave that Ikhtyandr uses to get between the sea and the hollowed-out cliff-face atop which his father’s house stands, correctly identifying said cave as the monster’s lair. And of at least equal importance, Ikhtyandr’s brief encounter with Gutiere has left him head over flippers in love with her, and he goes into town to seek her out almost immediately after Olsen concludes his visit with Salvator. Ikhtyandr’s activities in the city will bring him sharply into conflict with Zurita in the boy’s human guise, just as the don’s get-richer-quick scheme will mean conflict with Ikhtyandr in his guise as the Sea Devil, for Gutiere is very receptive to her mysterious new suitor.

It’s kind of like a gender-twist version of “The Little Mermaid,” only with class conflict, mad science, and Russian-language mariachi music— in other words, something the world never knew it had been missing until the day it showed up unbidden on the doorstep. And make no mistake, the world (or at least that section of it whose leaders were signatories to the Warsaw Pact) was indeed grateful for this hyper-dense nugget of concentrated strangeness, thronging the theaters in astonishing numbers. Reportedly, 65 million tickets to Amphibian Man were sold in 1962! My best guess as to the secret of Amphibian Man’s success is that it brings together so many seemingly incompatible elements, and yet does more or less right by all of them. Its outre mad science, though still common enough in the West in the early 1960’s, seems to have represented a rather sharp break with the more sober and self-conscious approach to sci-fi that dominated the genre in Soviet hands. Combined with a central conflict straight out of a fairy tale, it makes for much more openly escapist entertainment than Russian audiences may have been accustomed to in movies set during the present day. On the other hand, Amphibian Man is an extremely thoughtful and, beneath the surface, even serious film. Had this movie been made anywhere else in the world, I would dismiss what I’m about to say as a monumental crock of shit. However, the Soviet Union was expressly founded upon an obsession with class struggle, so I don’t believe I’m hallucinating when I observe that through its four principal male characters, Amphibian Man finds all sorts of fairly credible things to say about social inequity and how best to combat it.

Pedro Zurita initially seems the most transparent, so we’ll deal with him first. It may look like mere lip-service to political orthodoxy when the villain is revealed to be an arrogant petty capitalist whose proportionate wealth enables him to purchase not only an unwilling bride, but even the subservience of the local police. In truth, however, Amphibian Man permits Zurita to have nuances that one would never expect to see in a simple stock black-hat, and for that reason, I think he deserves a closer examination. That the filmmakers intend to treat Zurita as a human being, and not just as the embodiment of everything they’ve been indoctrinated to hate, first becomes apparent once the marriage between him and Gutiere is a done deal. Rather than accept Pedro as her husband in any sense save the purely legal, Gutiere takes a separate room from him, and barricades herself inside it. One might expect Zurita simply to break his way in and take his bride by force, but instead he parks himself miserably on the sofa outside and tries to cajole her into letting him in. Even the derisive taunting of the mustachioed middle-aged lady whom I take to be his mother is insufficient to rouse Pedro to anything more aggressive than an agonized sulk. Clearly, Zurita really does love Gutiere, and is both bewildered and sick at heart over her inability (or perhaps refusal would be the better term) to love him in return. On a related note, a confrontation with Salvator after Zurita has learned the truth about Ikhtyandr, in which Zurita offers to get the scientist released from jail if he’ll take on a lucrative position as his personal biological engineer, yields not the expected outburst of rage when Salvator refuses to cooperate, but one of flusterment and total incomprehension. Together, these incidents suggest that Zurita is less personally evil than just plain incapable of understanding that there are some things his money cannot— and should not be able to— buy. The verdict is a remarkably forgiving one: he is the product of a system built on exploitation as much as he is its representative, and a figure to be pitied even as he is opposed.

Zurita’s main opponents, of course, are Ikhtyandr and Olsen. As Don Pedro’s romantic rival, Ikhtyandr naturally clashes with him primarily on an emotional basis— and this can be said also of Ikhtyandr’s dealings with the order of which Zurita is a part. Ikhtyandr’s nature is defined by his boundless and often somewhat irrational generosity. First and foremost, he is generous with his feelings. He falls for Gutiere at first sight, and spends the rest of the movie naively taking nearly insane risks to his personal safety in order to be with her. Meanwhile, accustomed to living amid the vast bounty of the sea, he has no concept of monetary value, and gives away fish, pearls, and his father’s cash to whomever seems to want them, whenever he has any to give. Alas, this means that Ikhtyandr is also a sitting duck for anyone who might ever try to take advantage of him, and virtually everybody except Gutiere and Olsen does. Amphibian Man seems to shake its head sadly at its title character, saying, “It’s beautiful, isn’t it? Pity it’ll never work…” Instead, nearly all of the effective opposition to Zurita and the corrupt authorities he has in his pocket comes from Olsen, who is much harder-headed than the haplessly beatific gill-boy. Anytime decisive action is called for— when Zurita and Baltazar fish Ikhtyandr out of the sea and keep him captive aboard the Medusa; when Salvator and Ikhtyandr are jailed on charges of piracy for the ensuing attack on Zurita’s ship; when somebody has to toil indefinitely at the thankless task of keeping an officially suppressed newspaper up and running— Olsen is the man to do it. There’s precious little romance in his motives, and none at all in his methods, but he’s got all the courage and competence a revolutionary could ask for, and his is the approach the movie seems to endorse.

Amphibian Man’s most surprising bit of subtext is its implicit stance on Salvator and his experiments, however. In case you hadn’t noticed, we’re talking about a man with a grandiose vision of a new world free from privation and exploitation, one that depends for its success upon the visionary’s ability to remake the basic nature of humankind. We’re also talking about a man who does not much concern himself with whether the beneficiaries of his genius actually want to be remade in accordance with that vision. For all practical purposes, we may as well be talking about the founding fathers of Bolshevism. And yet Salvator is unmistakably portrayed as being in thrall to a dangerous pipe-dream, and Amphibian Man ends with him atoning for his messianic folly with a gesture of self-sacrifice that could scarcely be less characteristic of a Lenin, a Stalin, or a Trotsky. Of course, the Twentieth Party Congress, at which Khrushchev delivered his famous “secret speech” condemning the excesses of the Stalin era, was already five years in the past in 1961, and de-Stalinization was well underway. Nevertheless, the fact remains that thousands of artists, writers, and filmmakers had been worked to death in the Gulags for making far less provocative subtextual statements than this, and Khrushchev himself was no slouch when it came to imprisoning people whose opinions he didn’t care for. Might it be, then, that some part of Amphibian Man’s appeal at the time was its success in having it both ways? For Soviet audiences, an ability to parse the unspoken ideological content of practically anything was nothing more nor less than a basic survival skill; might such audiences have responded to this movie in part for delivering an acceptably socialistic message while sneaking a veiled critique of the Revolutionary generation in through the back door? I don’t know, but it sure caught my attention.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact