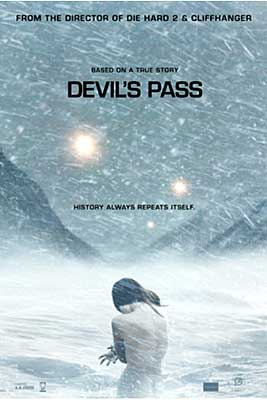

Devil’s Pass/The Dyatlov Pass Incident (2013) **½

Devil’s Pass/The Dyatlov Pass Incident (2013) **½

These past couple months, Juniper and I have been watching a lot of 1970’s “documentaries” about “unsolved” “mysteries.” You know the kind of films I mean: aliens built the pyramids, Nostradamus predicted World War II, Jack the Ripper was really the Loch Ness Monster. We’ve both got sort of a love-hate relationship with that stuff, because it calls attention to some of the weirdest, coolest, most intellectually stimulating puzzles of history and science, but by leaping immediately to lurid bullshit explanations, it closes off exactly the avenues of inquiry that make the phenomena under consideration so interesting in the first place. And the anthropological subgenre specifically tends to be racist as fuck on top of it all. I bring up that recent pattern in our viewing because Devil’s Pass— a movie I’m watching while Juniper’s out of town because she wanted absolutely nothing to do with it— turns out to fit in with it quite nicely. It’s like a double-length episode of “In Search Of” that freely acknowledges its fictionality.

The real-life anomaly that Devil’s Pass purports to explain is the Dyatlov Pass Incident. At the end of January 1959, Igor Dyatlov led nine other post-collegiate mountaineering enthusiasts on a grueling cross-country skiing trek across the far northern reaches of the Ural Mountains. One member of the group got sick at the last minute, and had to stay behind in Vizhal, the northernmost permanent settlement in that part of Russia. The others were never seen alive again. No one really knows what happened to Dyatlov and his companions on the night of February 2nd, but the scene that confronted the rescue parties at their final campsite was bizarre. The mountaineers’ tent had been torn open from the inside, and the condition of the bodies indicated that they had tried to get away from something in a hurry. Most of the corpses were barely dressed, none of them were wearing their climbing boots or snowshoes, and the few that were bundled up halfway-adequately were wearing oddball mishmashes of each other’s cold-weather gear. For six of the victims, hypothermia was obvious enough as a cause of death, but the other three had skull and/or rib fractures that could have been lethal in themselves— only none of them showed the kind of soft-tissue damage that ought to have accompanied such injuries. On the other hand, Lyudmila Dubinina, one of the pair with broken ribs, was missing her tongue, eyes, and lips. Meanwhile, there were reports of strange orange fireballs in the sky over the mountains that night, and on several others during the ensuing months, and some descriptions of the campsite mention a scattering of unidentifiable scrap metal. Weirdest of all, the clothes which several of the corpses were wearing registered inexplicably high levels of radioactivity. The inquest issued a vague non-verdict, and all files related to the incident were sealed for more than 30 years. That wasn’t a smart move if the object was to deflect outside attention from the case, but you know modern governments. If there’s a sketchy, secretive, dishonest-looking way to do something, that’s the way it’ll be done. A variety of theories, ranging from the mundane to the wildly conspiratorial, have been put forward in the years since to explain what happened, but Devil’s Pass commendably doesn’t follow any of them. Instead, writer Vikram Weet concocts a truly whackaloon narrative all his own, involving ancient aliens, military malfeasance, time travel, and three or four kitchen sinks.

American college student Holly King (Holly Goss) became enraptured with the Dylatlov Pass Incident when she wrote a paper on it for one of her psychology professors, Martha Kittle (World War Z’s Jane Perry). It’s an interest she shares with her classmate, wide-ranging conspiracy crazy Jensen Day (Hollow’s Matt Stokoe), and since it happens that Jensen is an amateur filmmaker, it was probably inevitably that the two of them would eventually decide to go to Russia in the hope of uncovering and documenting the real story. (Yeah, that means Devil’s Pass is going to be a found-footage movie. And like virtually all such films, it can’t quite force itself to color within the lines of that conceit once the stakes of the story start rising toward a climactic pitch.) They recruit the brawny and tough-as-nails Denise Evers (Gemma Atkinson, from Night of the Wolf and Night of the Living Dead 3-D) to be their audio tech, and daredevil mountaineers Andy Thatcher (Ryan Hawley) and J.P. Hauser (Luke Albright) to make sure they don’t die like the people whose fate they’re investigating. Then it’s off to Russia— where most of them will die almost exactly like the people whose fate they’re investigating.

The first warning sign comes when the filmmakers seek out Piotr Karov (Boris Stapanov), this movie’s fictional analogue to the guy who survived the trip by getting too sick to go on it, at the nursing home where he’s been living for many years. The orderlies refuse Holly and her colleagues entry, claiming that Karov died recently, but they’re obviously hiding something. Sure enough, as the flummoxed students stand around outside the nursing home trying to figure out their next move, Jensen catches sight of someone in an upstairs window holding up hand-written sign reading “Уходите.” None of them reads a word of Russian, so it’ll be another couple days before they learn what that means: “Stay away.” What seems certain up front is that the message was intended for them, and if that’s so, then it’s a safe bet the guy in the window was Piotr Karov.

The kids have a lucky break that night, when they stop in at a bar in the hope of finding someone to take them to Vizhal to begin the last leg of their journey. One of the regulars there is a man named Sergei (Nikolay Butenin), whose mother (Nelly Nielsen) lives in Vizhal. Better yet, Sergei’s mom was one of the volunteers who served in the Dyatlov Pass rescue effort all those years ago. Alya is still sharp as a tack despite her age, and Holly has no trouble getting her to talk to the camera about what she saw back then. Most of what she says is old news to Holly and Jensen, but one detail is so unexpected as to call into question everything they thought they knew about event. Alya says she saw eleven dead bodies at the pass, rather than the nine of the official reports. The entire Dyatlov party numbered only nine once Karov was sidelined, so who could those two surplus corpses have been?

The climb to the pass and the ensuing night at the Dyatlov party’s own campsite comprise the Blair Witch-iest part of the film. Come to think of it, there’s very nearly a point-for-point correspondence between the weird shit that happens on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl and the weird shit that happened in the woods around Burkittsville. The magnetic anomaly that renders the team’s compasses and cell phones useless has an effect equivalent to Mike throwing away the map in The Blair Witch Project. The impossibly good time Holly and company make on their way up the mountain echoes, in an equal-and-opposite way, the day Heather and company spend hiking due south by their compasses, only to discover that they’ve somehow traveled in a complete circle. The recurring patches of huge, bare footprints— footprints which lead neither into nor out of anywhere, but merely meander about in discrete areas, as if whatever made them simply appeared and disappeared— are this movie’s equivalent to the other’s sinister cairns and stick figures. Devil’s Pass even has a moment when the mountaineers stumble upon a gruesome piece of severed flesh, left for them to find like a housecat’s hunting trophy. And of course the effect that those manifestations have on the climbers’ nerves will be familiar to any veteran of The Blair Witch Project. Devil’s Pass does, however, have one trick up its sleeve that its model never played (albeit not for lack of trying). Closely watch the background whenever there’s a fault in the video image, and you’ll see something moving around unnoticed by the protagonists.

Devil’s Pass develops its own personality again shortly after Holly and Jensen discover this movie’s equivalent to the Rustin Parr house, an incongruous steel door set into the living rock of the mountainside, exactly like in a recurring dream that she had just finished telling him about. The pair decide to keep quiet about this latest puzzle until the morning, but by then everybody has more pressing concerns. Shortly before dawn, the climbers are awakened by what sounds like an explosion, and an avalanche buries their tent and supplies. It also buries Denise, who was still scrambling into her clothes as she tried to flee the onrushing snow. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Arguably even worse for the party as a whole is what happens to Andy. He gets a compound fracture of the tibia, putting one of the team’s two wilderness survival experts out of action just when he’s needed most. Jensen fires off a signal flare in the hope of summoning help from Vizhal, but what the flare brings instead is a pair of rifle-armed soldiers who start taking shots at the snooping Americans as soon as it becomes obvious that only one of them died in the avalanche. Andy tries to hold them off with the flare gun while the others flee, but the only reachable shelter anywhere nearby is behind that door in the mountain. Obviously the soldiers don’t want Holly publicizing whatever secrets lie within the mysterious bunker, but it suits them fine if she, Jensen, and J.P. hide out there. The door opens only from the outside, so it’s not like they’ll be going anyplace. Nor are they all that the soldiers are locking in. Those things we’ve seen skulking around the mountain— the ones with the huge feet and the macabre sense of humor— have been living in the bunker since 1959, when they played a part in the Dyatlov Pass Incident, and they were never supposed to have gotten out. Holly and Jensen (but not J.P., I’m afraid) are about to learn what they set out to, at which point they’ll realize that the Incident never really ended. Indeed, there’s an important sense in which it hasn’t yet begun.

It was with no little dismay that I greeted the name Renny Harlin in the credits to Devil’s Pass. In fact, that might have been even more dismaying than the realization that this movie was doing the found footage thing. I mean, we’re talking about a guy for whom A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master counts as a career highlight. But while Devil’s Pass lived all the way down to most of my expectations for found-footage horror movies, it turned out to be probably the best thing I’ve ever seen from Harlin. Hailing as he does from Finland, Harlin ought to have an instinctive appreciation for the power of forbidding, frozen landscapes, and he surely makes adept use of them here. Similarly adept is his exploitation of the bunker’s internal architecture, which is somehow too cramped and too spacious at the same time. What’s really shocking, though, is the pacing of Devil’s Pass, which is confidently relaxed and totally at ease in the absence of explosions and motor vehicle chases. Even The Dream Master was, in its way, a busy, noisy film, built around a succession of high-concept set-pieces, so I was unprepared for Devil’s Pass to take its time and build up suspense, one wrong detail at a time. Nor did I expect to see Harlin giving the five mostly inexperienced young actors of the core cast the space to forge themselves into a genuine ensemble. For all the friction between them, Holly’s film crew comes across as a fairly sturdy unit that just got in over their heads, rather than the usual bunch of bickering bozos.

Vikram Weet deserves props, too, for bothering to learn many of the lessons that previous found footage films were offering to teach. Considering what an overt Blair Witch Project riff this is, it’s especially significant that Devil’s Pass invests so heavily in familiarizing the audience with the mystery that Holly and company have come to investigate. The vagueness of the legend of the Blair Witch remains one of my principal complaints with that film, but a person could come to Devil’s Pass knowing nothing at all about the Dyatlov Pass Incident, and be up to speed on the basics by the time the protagonists’ plane touches down in Russia. Meanwhile, Weet commendably follows the examples of [REC] and Cloverfield by building in scenes where the camera’s night vision setting becomes both a means for generating jump scares and an essential tool for character survival. And although this is a small thing, and could equally well be Weet’s or Harlin’s doing, Devil’s Pass is full of instances in which the person doing the filming puts the camera down. Sure, it strains credulity a little that they always just happen to set it down pointed in the correct direction to catch the next plot development, but my disbelief suspenders have a much easier time lifting that than they do the typical found-footage trope of the cameraman who keeps actively shooting no matter what. It’s just a pity Devil’s Pass then blows it by coming to a conclusion that makes it impossible to believe this footage ever getting out to be seen by anybody, let alone in the form presented here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact